Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * ▲ | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

19 Feb 2024

Population genetics of Glossina palpalis gambiensis in the sleeping sickness focus of Boffa (Guinea) before and after eight years of vector control: no effect of control despite a significant decrease of human exposure to the diseaseMoise S. Kagbadouno, Modou Séré, Adeline Ségard, Abdoulaye Dansy Camara, Mamadou Camara, Bruno Bucheton, Jean-Mathieu Bart, Fabrice Courtin, Thierry de Meeûs, Sophie Ravel https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.25.550445Reaching the last miles for transmission interruption of sleeping sickness in Guinea: follow-up of achievements and policy making using microsatellites-based population geneticsRecommended by Hugues Nana Djeunga based on reviews by Fabien HALKETT and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Fabien HALKETT and 2 anonymous reviewers

Thanks to the coordinated and sustained efforts of national control programs, the World Health Organization (WHO), bilateral cooperation and nongovernmental organizations, the incidence of Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT), better known as sleeping sickness, has drastically decreased during the last two decades (WHO, 2023a). Indeed, between 1999 and 2022, the reported number of new cases of the chronic form of sleeping sickness (Trypanosoma brucei gambiense) fell by 97% (from 27 862 to 799), and the number of newly reported cases of the acute form of HAT (Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense) fell by 94% (from 619 to 38) (WHO, 2023b). These encouraging trends led the WHO to target this debilitating and highly fatal (if untreated) vector-borne parasitic disease for elimination as a public health problem by 2020, and for interruption of transmission (zero case) by 2030 (WHO, 2021, WHO, 2023a). However, the disease is persisting in many foci, and even some cases of resurgence have been documented after unfortunate events such as war or pandemics (Moore et al., 1999; Sah et al., 2023. Simarro et al). Although effective control measures, diagnosis and treatment are complex and require specific skills (WHO, 2023), especially in a context which animal reservoirs, including hidden reservoirs, can contribute to the maintenance/persistence of infection (Welburn and Maudlin, 2012; Camara et al., 2021). Vector control therefore appears as a viable alternative to accelerate sleeping sickness transmission interruption, and WHO has identified some critical actions for HAT elimination, including the coordination of vector control and animal trypanosomiasis management among countries, stakeholders and other sectors (e.g. tourism and wildlife) through multisectoral national bodies to maximize synergies (WHO, 2021). The paper by Kagbadouno and Collaborators (2024) uses microsatellite markers genotyping and population genetics tools to investigate the impact of 11 years of tiny target-based vector control on the population biology of Glossina palpalis gambiensis in Boffa, one of the three active sleeping sickness foci in Guinea (Kagbadouno et al., 2012). Although vector control significantly reduced the apparent densities of tsetse flies (and therefore the human exposure to the vector) as well as the prevalence and incidence of the disease in the Boffa HAT focus (Courtin et al., 2015), no genetic signature of vector control was observed as no difference in population size, before and after the onset of the control policy, was found. The authors then provided national programs and implementing partners with indications on the actions to be taken to (i) maintain the achievements of vector control (thus avoiding rebound/resurgence as was experienced in the past (Franco et al., 2014), and (ii) accelerate the momentum towards elimination by for example combining these vector control efforts with medical surveys for case detection and treatment, in line with WHO recommendations (WHO, 2021). References Camara M, Soumah AM, Ilboudo H, Travaillé C, Clucas C, Cooper A, Kuispond Swar NR, Camara O, Sadissou I, Calvo Alvarez E, Crouzols A, Bart JM, Jamonneau V, Camara M, MacLeod A, Bucheton B, Rotureau B. Extravascular Dermal Trypanosomes in Suspected and Confirmed Cases of gambiense Human African Trypanosomiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Jul 1;73(1):12-20. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa897 Courtin F, Camara M, Rayaisse JB, Kagbadouno M, Dama E, Camara O, Traore IS, Rouamba J, Peylhard M, Somda MB, Leno M, Lehane MJ, Torr SJ, Solano P, Jamonneau V, Bucheton B (2015) Reducing human-tsetse contact significantly enhances the efficacy of sleeping sickness active screening campaigns: a promising result in the context of elimination. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003727 Franco JR, Simarro PP, Diarra A, Jannin JG. (2014) Epidemiology of human African trypanosomiasis. Clin Epidemiol. 6:257-75. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S39728 Kagbadouno, M. S., Séré, M., Ségard, A., Camara, A. D., Camara, M., Bucheton, B., ... & Ravel, S. (2023). Population genetics of Glossina palpalis gambiensis in the sleeping sickness focus of Boffa (Guinea) before and after eight years of vector control: no effect of control despite a significant decrease of human exposure to the disease. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.25.550445 Kagbadouno MS, Camara M, Rouamba J, Rayaisse JB, Traoré IS, Camara O, Onikoyamou MF, Courtin F, Ravel S, De Meeûs T, Bucheton B, Jamonneau V, Solano P (2012) Epidemiology of sleeping sickness in boffa (Guinea): where are the trypanosomes? PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 6, e1949. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001949 Moore A, Richer M, Enrile M, Losio E, Roberts J, Levy D. Resurgence of sleeping sickness in Tambura County, Sudan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999 Aug;61(2):315-8. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.315 Sah R, Mohanty A, Rohilla R, Padhi BK. A resurgence of Sleeping sickness amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: Correspondence. Int J Surg Open. 2023 Apr;53:100604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijso.2023.100604 Welburn SC, Maudlin I. Priorities for the elimination of sleeping sickness. Adv Parasitol. 2012;79:299-337. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-398457-9.00004-4 World Health Organization, 2021. Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: a road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. ISBN: 978 92 4 001035 2. 196p. World Health Organization, 2023a. Trypanosomiasis, human African (sleeping sickness): key facts. Accessed at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/trypanosomiasis-human-african-(sleeping-sickness) on February 19, 2023. World Health Organization, 2023b. Human African Trypanosomiasis, (sleeping sickness): the global health observatory. Accessed at https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/human-african-trypanosomiasis on February 19, 2023. | Population genetics of *Glossina palpalis* gambiensis in the sleeping sickness focus of Boffa (Guinea) before and after eight years of vector control: no effect of control despite a significant decrease of human exposure to the disease | Moise S. Kagbadouno, Modou Séré, Adeline Ségard, Abdoulaye Dansy Camara, Mamadou Camara, Bruno Bucheton, Jean-Mathieu Bart, Fabrice Courtin, Thierry de Meeûs, Sophie Ravel | <p style="text-align: justify;">Human African trypanosomosis (HAT), also known as sleeping sickness, is still a major concern in endemic countries. Its cyclical vector are biting insects of the genus Glossina or tsetse flies. In Guinea, the mangro... | Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Evolution of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Parasites, Population genetics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors | Hugues Nana Djeunga | 2023-07-29 13:24:52 | View | ||

07 Feb 2023

Three-way relationships between gut microbiota, helminth assemblages and bacterial infections in wild rodent populationsMarie Bouilloud, Maxime Galan, Adelaide Dubois, Christophe Diagne, Philippe Marianneau, Benjamin Roche, Nathalie Charbonnel https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.23.493084Unveiling the complex interactions between members of gut microbiomes: a significant advance provided by an exhaustive study of wild bank volesRecommended by Thomas Pollet based on reviews by Jason Anders and 1 anonymous reviewerThe gut of vertebrates is a host for hundreds or thousands of different species of microorganisms named the gut microbiome. This latter may differ greatly in natural environments between individuals, populations and species (1). The vertebrate gut microbiome plays key roles in host fitness through functions including nutrient acquisition, immunity and defense against infectious agents. While bank voles are small mammals potentially reservoirs of a large number of infectious agents, questions about the links between their gut microbiome and the presence of pathogens are scarcely addressed. In this study, Bouilloud et al. (2) used complementary analyses of community and microbial ecology to (i) assess the variability of gut bacteriome diversity and composition in wild populations of the bank vole Myodes glareolus collected in four different sites in Eastern France and (ii) evaluate the three-way interactions between the gut bacteriota, the gastro-intestinal helminths and pathogenic bacteria detected in the spleen. Authors identified important variations of the gut bacteriota composition and diversity among bank voles mainly explained by sampling localities. They found positive correlations between the specific richness of both the gut bacteria and the helminth community, as well as between the composition of these two communities, even when accounting for the influence of geographical distance. The helminths Aonchotheca murissylvatici, Heligmosomum mixtum and the bacteria Bartonella sp were the main taxa associated with the whole gut bacteria composition. Besides, changes in relative abundance of particular gut bacterial taxa were specifically associated with other helminths (Mastophorus muris, Catenotaenia henttoneni, Paranoplocephala omphalodes and Trichuris arvicolae) or pathogenic bacteria. Infections with Neoehrlichia mikurensis, Orientia sp, Rickettsia sp and P. omphalodes were especially associated with lower relative abundance of members of the family Erysipelotrichaceae (Firmicutes), while coinfections with higher number of bacterial infections were associated with lower relative abundance of members of the Bacteroidales family (Bacteroidetes). As pointed out by both reviewers, this study represents a significant advance in the field. I would like to commend the authors for this enormous work. The amount of data, analyses and results is considerable which has sometimes complicated the understanding of the story at the beginning of the evaluation process. Thanks to constructive scientific interactions with both reviewers through the two rounds of evaluation, the authors have efficiently addressed the reviewer's concerns and improved the manuscript, making this great story easier to read. The innovative results of this study emphasize the complex interlinkages between gut bacteriome and infections in wild animal populations and I strongly recommend this article for publication In Peer Community Infections. References (1) Vujkovic-Cvijin I, Sklar J, Jiang L, Natarajan L, Knight R, Belkaid Y (2020) Host variables confound gut microbiota studies of human disease. Nature, 587, 448–454. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2881-9 (2) Bouilloud M, Galan M, Dubois A, Diagne C, Marianneau P, Roche B, Charbonnel N (2023) Three-way relationships between gut microbiota, helminth assemblages and bacterial infections in wild rodent populations. biorxiv, 2022.05.23.493084, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.23.493084 | Three-way relationships between gut microbiota, helminth assemblages and bacterial infections in wild rodent populations | Marie Bouilloud, Maxime Galan, Adelaide Dubois, Christophe Diagne, Philippe Marianneau, Benjamin Roche, Nathalie Charbonnel | <p>Background</p> <p>Despite its central role in host fitness, the gut microbiota may differ greatly between individuals. This variability is often mediated by environmental or host factors such as diet, genetics, and infections. Recently, a part... | Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecohealth, Interactions between hosts and infectious agents/vectors, Reservoirs, Zoonoses | Thomas Pollet | 2022-05-25 10:13:23 | View | ||

19 Jul 2023

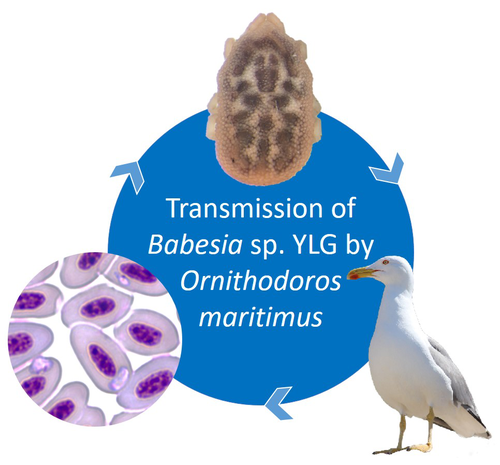

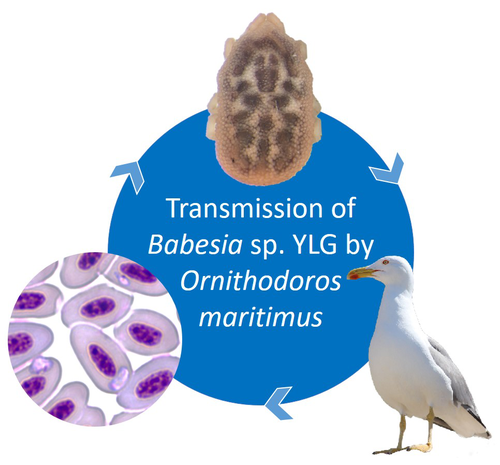

A soft tick vector of Babesia sp. YLG in Yellow-legged gull (Larus michahellis) nestsClaire Bonsergent, Marion Vittecoq, Carole Leray, Maggy Jouglin, Marie Buysse, Karen D. McCoy, Laurence Malandrin https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.24.534071A four-year study reveals the potential role of the soft tick Ornithodoros maritimus in the transmission and circulation of Babesia sp. YLG in Yellow-legged gull colonies.Recommended by Thomas Pollet based on reviews by Hélène Jourdan-Pineau and Tahar KernifWorldwide, ticks and tick-borne diseases are a persistent example of problems at the One Health interface between humans, wildlife, and environment (1, 2). The management and prevention of ticks and tick-borne diseases require a better understanding of host, tick and pathogen interactions and thus get a better view of the tick-borne pathosystems. In this study (3), the tick-borne pathosystem included three component species: first a seabird host, the Yellow-legged gull (YLG - Larus michahellis, Laridae), second a soft nidicolous tick (Ornithodoros maritimus, Argasidae, syn. Alectorobius maritimus) known to infest this host and third a blood parasite (Babesia sp. YLG, Piroplasmidae). In this pathosystem, authors investigated the role of the soft tick, Ornithodoros maritimus, as a potential vector of Babesia sp. YLG. They analyzed the transmission of Babesia sp. YLG by collecting different tick life stages from YLG nests during 4 consecutive years on the islet of Carteau (Gulf of Fos, Camargue, France). Ticks were dissected and organs were analyzed separately to detect the presence of Babesia sp DNA and to evaluate different transmission pathways. While the authors detected Babesia sp. YLG DNA in the salivary glands of nymphs, females and males, this result reveals a strong suspicion of transmission of the parasite by the soft tick. Babesia sp. YLG DNA was also found in tick ovaries, which could indicate possible transovarial transmission. Finally, the authors detected Babesia sp. YLG DNA in several male testes and in endospermatophores, and notably in a parasite-free female (uninfected ovaries and salivary glands). These last results raise the interesting possibility of sexual transmission from infected males to uninfected females. As pointed out by both reviewers, this is a nice study, well written and easy to read. All the results are new and allow to better understand the role of the soft tick, Ornithodoros maritimus, as a potential vector of Babesia sp. YLG. They finally question about the degree to which the parasite can be maintained locally by ticks and the epidemiological consequences of infection for both O. maritimus and its avian host. For all these reasons, I chose to recommend this article for Peer Community In Infections. References

| A soft tick vector of *Babesia* sp. YLG in Yellow-legged gull (*Larus michahellis*) nests | Claire Bonsergent, Marion Vittecoq, Carole Leray, Maggy Jouglin, Marie Buysse, Karen D. McCoy, Laurence Malandrin | <p style="text-align: justify;"><em>Babesia </em>sp. YLG has recently been described in Yellow-legged gull (<em>Larus michahellis</em>) chicks and belongs to the Peircei clade in the new classification of Piroplasms. Here, we studied <em>Babesia <... |  | Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Eukaryotic pathogens/symbionts, Interactions between hosts and infectious agents/vectors, Parasites, Vectors | Thomas Pollet | 2023-03-29 14:33:40 | View | |

21 Sep 2023

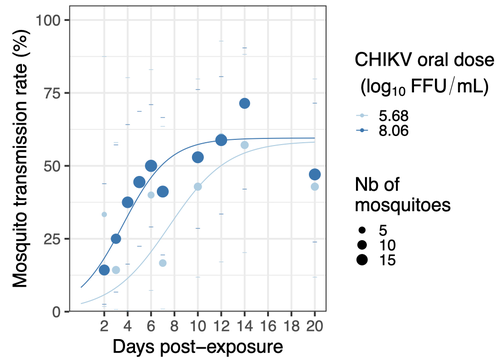

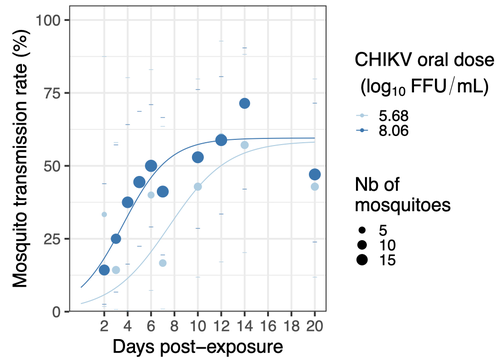

Chikungunya intra-vector dynamics in Aedes albopictus from Lyon (France) upon exposure to a human viremia-like dose range reveals vector barrier permissiveness and supports local epidemic potentialBarbara Viginier, Lucie Cappuccio, Celine Garnier, Edwige Martin, Carine Maisse, Claire Valiente Moro, Guillaume Minard, Albin Fontaine, Sebastian Lequime, Maxime Ratinier, Frederick Arnaud, Vincent Raquin https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.06.22281997Fill in one gap in our understanding of CHIKV intra-vector dynamicsRecommended by Sara Moutailler based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

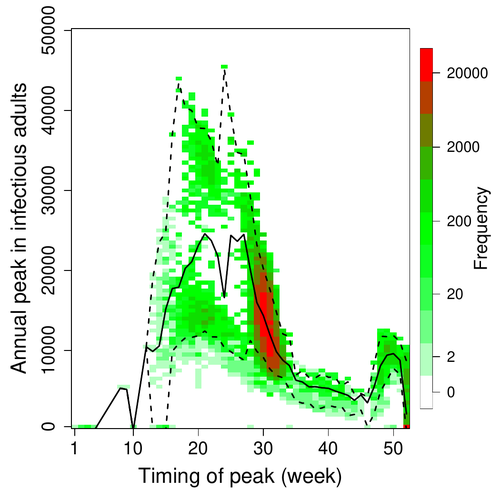

Mosquitoes are first vector of pathogen worldwide and transmit several arbovirus, most of them leading to major outbreaks (1). Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a perfect example of the “explosive type” of arbovirus, as observed in La Réunion Island in 2005-2006 (2-6) and also in the outbreak of 2007 in Italy (7), both vectorized by Ae. albopictus. Being able to better understand CHIKV intra-vector dynamics is still of major interest since not all chikungunya strain are explosive ones (8). In this study (9), the authors have evaluated the vector competence of a local strain of Aedes albopictus (collected in Lyon, France) for CHIKV. They evaluated infection, dissemination and transmission dynamics of CHIKV using different dose of virus in individual mosquitoes from day 2 to day 20 post exposure, by titration and quantification of CHIKV RNA load in the saliva. As highlighted by both reviewers, the most innovative idea in this study was the use of three different oral doses trying to span human viraemia detected in two published studies (10-11), doses that were estimated through their model of human CHIKV viremia in the blood. They have found that CHIKV dissemination from the Ae. albopictus midgut depends on the interaction between time post-exposure and virus dose (already highlighted by other international publications). Then their results were implemented in the agent-based model nosoi to estimate the epidemic potential of CHIKV in a French population of Ae. albopictus, using realistic vectorial capacity parameters. To conclude, the authors have discussed the importance of other parameters that could influence vector competence as mosquito microbiota and temperature, parameters that need also to be estimated in local mosquito population to improve the risk assessment through modelling. As pointed out by both reviewers, this is a nice study, well written and easy to read. These results allow filling in another gap of our understanding of CHIKV intra-vector dynamics and highlight the epidemic potential of CHIKV upon transmission by Aedes albopictus in mainland France. For all these reasons, I chose to recommend this article for Peer Community In Infections. References 1. Marine Viglietta, Rachel Bellone, Adrien Albert Blisnick, Anna-Bella Failloux. (2021). Vector Specificity of Arbovirus Transmission. Front Microbiol Dec 9;12:773211. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.773211 2. Schuffenecker I, Iteman I, Michault A, Murri S, Frangeul L, Vaney M-C, Lavenir R, Pardigon N, Reynes J-M, Pettinelli F, Biscornet L, Diancourt L, Michel S, Duquerroy S, Guigon G, Frenkiel M-P, Bréhin A-C, Cubito N, Desprès P, Kunst F, Rey FA, Zeller H, Brisse S. (2006). Genome Microevolution of Chikungunya viruses Causing the Indian Ocean Outbreak. 2006. PLoS Medicine, 3, e263. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030263 3. Bonilauri P, Bellini R, Calzolari M, Angelini R, Venturi L, Fallacara F, Cordioli P, 687 Angelini P, Venturelli C, Merialdi G, Dottori M. (2008). Chikungunya Virus in Aedes albopictus, Italy. Emerging Infectious 689 Diseases, 14, 852–854. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1405.071144 4. Pagès F, Peyrefitte CN, Mve MT, Jarjaval F, Brisse S, Iteman I, Gravier P, Tolou H, Nkoghe D, Grandadam M. (2009). Aedes albopictus Mosquito: The Main Vector of the 2007 Chikungunya Outbreak in Gabon. PLoS ONE, 4, e4691. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004691 5. Paupy C, Kassa FK, Caron M, Nkoghé D, Leroy EM (2012) A Chikungunya Outbreak Associated with the Vector Aedes albopictus in Remote Villages of Gabon. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 12, 167–169. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2011.0736 6. Mombouli J-V, Bitsindou P, Elion DOA, Grolla A, Feldmann H, Niama FR, Parra H-J, Munster VJ. (2013). Chikungunya Virus Infection, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo, 2011. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 19, 1542–1543. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1909.130451 7. Venturi G, Luca MD, Fortuna C, Remoli ME, Riccardo F, Severini F, Toma L, Manso MD, Benedetti E, Caporali MG, Amendola A, Fiorentini C, Liberato CD, Giammattei R, Romi R, Pezzotti P, Rezza G, Rizzo C. (2017). Detection of a chikungunya outbreak in Central Italy, August to September 2017. Eurosurveillance, 22, 17–00646. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.es.2017.22.39.17-00646 8. de Lima Cavalcanti, T.Y.V.; Pereira, M.R.; de Paula, S.O.; Franca, R.F.d.O. (2022). A Review on Chikungunya Virus Epidemiology, Pathogenesis and Current Vaccine Development. Viruses 2022, 14, 969. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14050969 9. Barbara Viginier, Lucie Cappuccio, Celine Garnier, Edwige Martin, Carine Maisse, Claire Valiente Moro, Guillaume Minard, Albin Fontaine, Sebastian Lequime, Maxime Ratinier, Frederick Arnaud, Vincent Raquin. (2023). Chikungunya intra-vector dynamics in Aedes albopictus from Lyon (France) upon exposure to a human viremia-like dose range reveals vector barrier permissiveness and supports local epidemic potential. medRxiv, ver.3, peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.06.22281997 10. Appassakij H, Khuntikij P, Kemapunmanus M, Wutthanarungsan R, Silpapojakul K (2013) Viremic profiles in CHIKV-infected cases. Transfusion, 53, 2567–2574. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03960.x 11. Riswari SF, Ma’roef CN, Djauhari H, Kosasih H, Perkasa A, Yudhaputri FA, Artika IM, Williams M, Ven A van der, Myint KS, Alisjahbana B, Ledermann JP, Powers AM, Jaya UA (2015) Study of viremic profile in febrile specimens of chikungunya in Bandung, Indonesia. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology, 74, 61–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2015.11.017 | Chikungunya intra-vector dynamics in *Aedes albopictus* from Lyon (France) upon exposure to a human viremia-like dose range reveals vector barrier permissiveness and supports local epidemic potential | Barbara Viginier, Lucie Cappuccio, Celine Garnier, Edwige Martin, Carine Maisse, Claire Valiente Moro, Guillaume Minard, Albin Fontaine, Sebastian Lequime, Maxime Ratinier, Frederick Arnaud, Vincent Raquin | <p>Arbovirus emergence and epidemic potential, as approximated by the vectorial capacity formula, depends on host and vector parameters, including the vector intrinsic ability to replicate then transmit the pathogen known as vector competence. Vec... |  | Epidemiology, Vectors, Viruses | Sara Moutailler | 2023-06-17 15:59:17 | View | |

24 Jan 2024

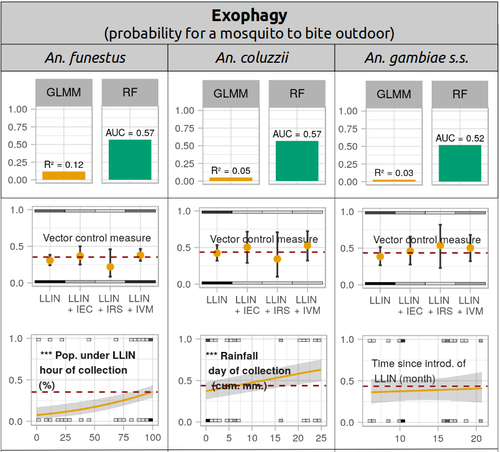

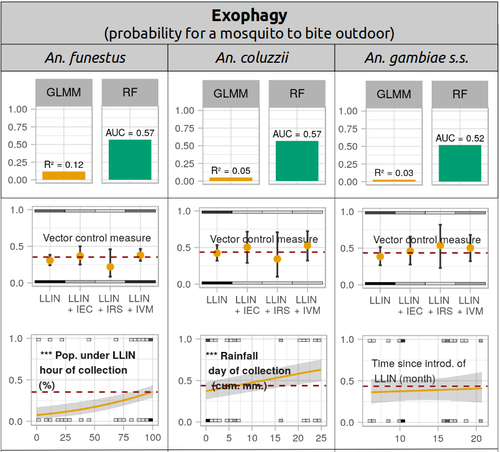

Physiological and behavioural resistance of malaria vectors in rural West-Africa : a data mining study to address their fine-scale spatiotemporal heterogeneity, drivers, and predictabilityPaul Taconet, Dieudonné Diloma Soma, Barnabas Zogo, Karine Mouline, Frédéric Simard, Alphonsine Amanan Koffi, Roch Kounbobr Dabiré, Cédric Pennetier, Nicolas Moiroux https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.20.504631Large and complete datasets, and modelling reveal the major determinants of physiological and behavioral insecticide resistance of malaria vectorsRecommended by Thierry DE MEEÛS based on reviews by Haoues Alout and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Haoues Alout and 1 anonymous reviewer

Parasites represent the most diverse and adaptable ecological group of the biosphere (Timm & Clauson, 1988; De Meeûs et al., 1998; Poulin & Morand, 2000; De Meeûs & Renaud, 2002). The human species is known to considerably alter biodiversity, though it hosts, and thus sustains the maintenance of a spectacular diversity of parasites (179 species for eukaryotic species only) (De Meeûs et al., 2009). Among these, the five species of malaria agents (genus Plasmodium) remain a major public health issue around the world. Plasmodium falciparum is the most prevalent and lethal of these (Liu et al., 2010). With a pick of up to 2 million deaths due to malaria in 2004, deaths decreased to around 1 million in 2010 (Murray et al., 2012), to reach 619,000 in 2021, most of which in sub-Saharan Africa, and 79% of which were among children aged under 5 years (World Health Organization, 2022). As stressed by Taconet et al. (2023), reduction in malaria deaths is attributable to control measures, in particular against its vectors (mosquitoes of the genus Anopheles). Nevertheless, the success of vector control is hampered by several factors (biological, environmental and socio-economic), and in particular by the great propensity of targeted mosquitoes to evolve physiological or behavioral avoidance of anti-vectorial measures. In their paper Taconet et al. (2023) aims at understanding what are the main factors that determine the evolution of insecticide resistance in several malaria vectors, in relation to the biological determinisms of behavioral resistance and how fast such evolutions take place. To tackle these objectives, authors collected an impressive amount of data in two rural areas of West Africa. With appropriate modeling, Taconet et al. discovered, among many other results, a predominant role of public health measures, as compared to agricultural practices, in the evolution of physiological resistance. They also found that mosquito foraging activities are mostly explained by host availability and climate, with a poor, if any, association with genetic markers of physiological resistance to insecticides. These findings represent an important contribution to the field and should help at designing more efficient control strategies against malaria.

References De Meeûs T, Michalakis Y, Renaud F (1998) Santa Rosalia revisited: or why are there so many kinds of parasites in “the garden of earthly delights”? Parasitology Today, 14, 10–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-4758(97)01163-0 De Meeûs T, Prugnolle F, Agnew P (2009) Asexual reproduction in infectious diseases. In: Lost Sex: The Evolutionary Biology of Parthenogenesis (eds Schön I, Martens K, van Dijk P), pp. 517-533. Springer, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2770-2_24 De Meeûs T, Renaud F (2002) Parasites within the new phylogeny of eukaryotes. Trends in Parasitology, 18, 247–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1471-4922(02)02269-9 Liu W, Li Y, Learn GH, Rudicell RS, Robertson JD, Keele BF, Ndjango JB, Sanz CM, Morgan DB, Locatelli S, Gonder MK, Kranzusch PJ, Walsh PD, Delaporte E, Mpoudi-Ngole E, Georgiev AV, Muller MN, Shaw GM, Peeters M, Sharp PM, Rayner JC, Hahn BH (2010) Origin of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in gorillas. Nature, 467, 420–425. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09442 Murray CJ, Rosenfeld LC, Lim SS, Andrews KG, Foreman KJ, Haring D, Fullman N, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Lopez AD (2012) Global malaria mortality between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. The Lancet, 379, 413–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60034-8 Poulin R, Morand S (2000) The diversity of parasites. Quarterly Review of Biology, 75, 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1086/393500 Taconet P, Soma DD, Zogo B, Mouline K, Simard F, Koffi AA, Dabire RK, Pennetier C, Moiroux N (2023) Physiological and behavioural resistance of malaria vectors in rural West-Africa : a data mining study to address their fine-scale spatiotemporal heterogeneity, drivers, and predictability. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.20.504631 Timm RM, Clauson BL (1988) Coevolution: Mammalia. In: 1988 McGraw-Hill yearbook of science & technology, pp. 212–214. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York. World Health Organization (2022) World malaria report 2022. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/365169/9789240064898-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

| Physiological and behavioural resistance of malaria vectors in rural West-Africa : a data mining study to address their fine-scale spatiotemporal heterogeneity, drivers, and predictability | Paul Taconet, Dieudonné Diloma Soma, Barnabas Zogo, Karine Mouline, Frédéric Simard, Alphonsine Amanan Koffi, Roch Kounbobr Dabiré, Cédric Pennetier, Nicolas Moiroux | <p>Insecticide resistance and behavioural adaptation of malaria mosquitoes affect the efficacy of long-lasting insecticide nets - currently the main tool for malaria vector control. To develop and deploy complementary, efficient and cost-effective... |  | Behaviour of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Pesticide resistance, Population genetics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Vectors | Thierry DE MEEÛS | Haoues Alout, Anonymous | 2023-07-03 11:29:10 | View |

28 Oct 2022

Development of nine microsatellite loci for Trypanosoma lewisi, a potential human pathogen in Western Africa and South-East Asia, and preliminary population genetics analysesAdeline Ségard, Audrey Romero, Sophie Ravel, Philippe Truc, Gauthier Dobigny, Philippe Gauthier, Jonas Etougbetche, Henri-Joel Dossou, Sylvestre Badou, Gualbert Houéménou, Serge Morand, Kittipong Chaisiri, Camille Noûs, Thierry deMeeûs https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6460010Preliminary population genetic analysis of Trypanosoma lewisiRecommended by Annette MacLeod based on reviews by Gabriele Schönian and 1 anonymous reviewerTrypanosoma lewisi is an atypical trypanosome species. Transmitted by fleas, it has a high prevalence and worldwide distribution in small mammals, especially rats [1]. Although not typically thought to infect humans, there has been a number of reports of human infections by T. lewisi in Asia including a case of a fatal infection in an infant [2]. The fact that the parasite is resistant to lysis by normal human serum [3] suggests that many people, especially immunocompromised individuals, may be at risk from zoonotic infections by this pathogen, particularly in regions where there is close contact with T. lewisi-infected rat fleas. Indeed, it is also possible that cryptic T. lewisi infections exist but have hitherto gone undetected. Such asymptomatic infections have been detected for a number of parasitic infections including the related parasite T. b. gambiense [4]. References

[2] Truc P, Büscher P, Cuny G, Gonzatti MI, Jannin J, Joshi P, Juyal P, Lun Z-R, Mattioli R, Pays E, Simarro PP, Teixeira MMG, Touratier L, Vincendeau P, Desquesnes M (2013) Atypical Human Infections by Animal Trypanosomes. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 7, e2256. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002256 [3] Lun Z-R, Wen Y-Z, Uzureau P, Lecordier L, Lai D-H, Lan Y-G, Desquesnes M, Geng G-Q, Yang T-B, Zhou W-L, Jannin JG, Simarro PP, Truc P, Vincendeau P, Pays E (2015) Resistance to normal human serum reveals Trypanosoma lewisi as an underestimated human pathogen. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology, 199, 58–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molbiopara.2015.03.007 [4] Büscher P, Bart J-M, Boelaert M, Bucheton B, Cecchi G, Chitnis N, Courtin D, Figueiredo LM, Franco J-R, Grébaut P, Hasker E, Ilboudo H, Jamonneau V, Koffi M, Lejon V, MacLeod A, Masumu J, Matovu E, Mattioli R, Noyes H, Picado A, Rock KS, Rotureau B, Simo G, Thévenon S, Trindade S, Truc P, Reet NV (2018) Do Cryptic Reservoirs Threaten Gambiense-Sleeping Sickness Elimination? Trends in Parasitology, 34, 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2017.11.008 [5] Ségard A, Roméro A, Ravel S, Truc P, Gauthier D, Gauthier P, Dossou H-J, Sylvestre B, Houéménou G, Morand S, Chaisiri K, Noûs C, De Meeûs T (2022) Development of nine microsatellite loci for Trypanosoma lewisi, a potential human pathogen in Western Africa and South-East Asia, and preliminary population genetics analyses. Zenodo, 6460010, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6460010 | Development of nine microsatellite loci for Trypanosoma lewisi, a potential human pathogen in Western Africa and South-East Asia, and preliminary population genetics analyses | Adeline Ségard, Audrey Romero, Sophie Ravel, Philippe Truc, Gauthier Dobigny, Philippe Gauthier, Jonas Etougbetche, Henri-Joel Dossou, Sylvestre Badou, Gualbert Houéménou, Serge Morand, Kittipong Chaisiri, Camille Noûs, Thierry deMeeûs | <p><em>Trypanosoma lewisi</em> belongs to the so-called atypical trypanosomes that occasionally affect humans. It shares the same hosts and flea vector of other medically relevant pathogenic agents as Yersinia pestis, the agent of plague. Increasi... |  | Animal diseases, Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Eukaryotic pathogens/symbionts, Evolution of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Microbiology of infections, Parasites, Population genetics of hosts, in... | Annette MacLeod | 2022-04-21 17:04:37 | View | |

03 Nov 2023

Longitudinal Survey of Astrovirus infection in different bat species in Zimbabwe: Evidence of high genetic Astrovirus diversityVimbiso Chidoti, Helene De Nys, Malika Abdi, Getrudre Mashura, Valerie Pinarello, Ngoni Chiweshe, Gift Matope, Laure Guerrini, Davies Pfulenyi, Julien Cappelle, Ellen Mwandiringana, Dorothee Misse, Gori Elizabeth, Mathieu Bourgarel, Florian Liegeois https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.14.536987High diversity and evidence for inter-species transmission in astroviruses surveyed from bats in ZibabwaeRecommended by Tim James based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersMost infectious diseases of humans are zoonoses, and many of these come from particularly species diverse reservoir taxa, such as bats, birds, and rodents (1). Because of our changing landscape, there is increased exposure of humans to wildlife diseases reservoirs, yet we have little basic information about prevalence, hotspots, and transmission factors of most zoonotic pathogens. Viruses are particularly worrisome as a public health risk due to their fast mutation rates and well-known cross-species transmission abilities. There is a global push to better survey wildlife for viruses (2), but these studies are difficult, and the problem is vast. Astroviruses (AstVs) comprise a diverse family of ssRNA viruses known from mammals and birds. Astroviruses can cause gastroenteritis in humans and are more common in elderly and young children, but the relationship of human to non-human Astroviridae as well as transmission routes are unclear. AstVs have been detected at high prevalence in bats in multiple studies (3,4), but it is unclear what factors, such as co-infecting viruses and bat reproductive phenology, influence viral shedding and prevalence. References 1. Mollentze N, Streicker DG. Viral zoonotic risk is homogenous among taxonomic orders of mammalian and avian reservoir hosts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020 Apr 28;117(17):9423-30. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1919176117 | Longitudinal Survey of Astrovirus infection in different bat species in Zimbabwe: Evidence of high genetic Astrovirus diversity | Vimbiso Chidoti, Helene De Nys, Malika Abdi, Getrudre Mashura, Valerie Pinarello, Ngoni Chiweshe, Gift Matope, Laure Guerrini, Davies Pfulenyi, Julien Cappelle, Ellen Mwandiringana, Dorothee Misse, Gori Elizabeth, Mathieu Bourgarel, Florian Liegeois | <p>Astroviruses (AstVs) have been discovered in over 80 animal species including diverse bat species and avian species. A study on Astrovirus circulation and diversity in different insectivorous and frugivorous chiropteran species roosting in tree... |  | Animal diseases, Epidemiology, Molecular genetics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Reservoirs, Viruses, Zoonoses | Tim James | 2023-04-18 14:58:43 | View | |

14 Feb 2024

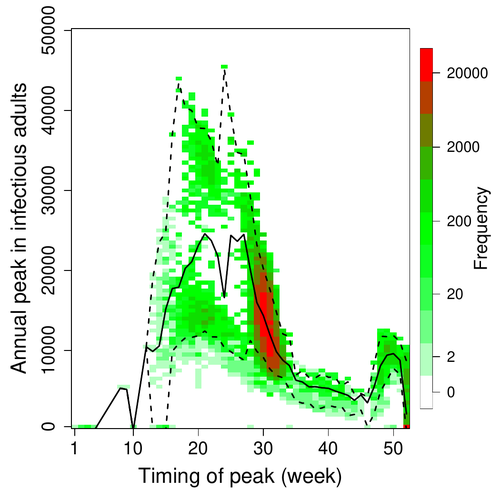

A Bayesian analysis of birth pulse effects on the probability of detecting Ebola virus in fruit batsDavid R.J. Pleydell, Innocent Ndong Bass, Flaubert Auguste Mba Djondzo, Dowbiss Meta Djomsi, Charles Kouanfack, Martine Peeters, Julien Cappelle https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.10.552777Epidemiological modeling to optimize the detection of zoonotic viruses in wild (reservoir) speciesRecommended by Aurelien Tellier based on reviews by Hetsron Legrace NYANDJO BAMEN and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Hetsron Legrace NYANDJO BAMEN and 1 anonymous reviewer

Various species of Ebolavirus have caused, and are still causing, zoonotic outbreaks and public health crises in Africa. Bats have long been hypothesized to be important reservoir populations for a series of viruses such as Hendra or Marburg viruses, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2) as well as Ebolaviruses [2, 3]. However the ecology of disease dynamics, disease transmission, and coevolution with their natural hosts of these viruses is still poorly understood, despite their importance for predicting novel outbreaks in human or livestock populations. The evidence that bats function as sylvatic reservoirs for Ebola viruses is yet only partial. Indeed, only few serological studies demonstrated the presence of Ebolavirus antibodies in young bats [4], albeit without providing positive controls of viral detection or identifying the viral species (via PCR). There is thus an unexplained discrepancy between serological data and viral detection [2, 4]. In this article, Pleydell et al. [1] use a modeling approach as well as published serological and age-structure (of the bat population) data to calibrate the model simulations. The study starts with the development of an age-structured epidemiological model which includes seasonal birth pulses and waning immunity, both generating pulses of Ebolavirus transmission within a colony of African straw-coloured fruit bats (Eidolon helvum). The epidemiological dynamics of such system of ordinary differential equations can generate annual outbreaks, skipped years or multi-annual cycles up to chaotic dynamics. Therefore, the calibration of the parameters, and the definition of biologically relevant priors, are key. To this aim, the serological data are obtained from a previous study in Cameroon [5], and the age structured of the bat population (birth and mortality) from a population study in Ghana [6]. These data are integrated into the Bayesian analysis and statistical framework to fit the model and generate predictions. In a nutshell, the authors show an overlap between the data and credibility intervals generated by the calibrated model, which thus explains well the seasonality of age-structure, namely changes in pup presence, number of lactating females, or proportion of juveniles in May. The authors can estimate that 76% of adults and 39% of young bats do survive each year, and infections are expected to last one and a half weeks. The epidemiological model predicts that annual birth pulses likely generate annual disease outbreaks, so that weeks 30 to 31 of each year, are predicted to be the best period to isolate the circulating Ebolavirus in this bat population. From the model predictions, the authors estimate the probability to have missed an infectious bat among all the samples tested by PCR being approximately of one per two thousands. The disease dynamics pattern observed in the serology data, and replicated by the model, is likely driven by seasonal pulses of young susceptible bats entering the population. This seasonal birth event increases the viral transmission, resulting in the observed peak of viral prevalence. With the inclusion of immunity waning and antibody persistence, the model results illuminate therefore why previous studies have detected only few positive cases by PCR tests, in contrast to the evidence from serological data. This study provides a first proof of principle that epidemiological modeling, despite its many simplifying assumptions, can be applied to wild species reservoirs of zoonotic diseases in order to optimize the design of field studies to detect viruses. Furthermore, such models can contribute to assess the probability and timing of zoonotic outbreaks in human or livestock populations. This article illustrates one of the manifold applications of mathematical theory of disease epidemiology to optimize sampling of pathogens/parasites or vaccine development and release [7, 8]. The further coupling of such models with population genetics theory and statistical inference methods (using parasite genome data) increasingly provide insights into the adaptation and evolution of parasites to human, crops and livestock populations [9, 10].

References [1] Pleydell D.R.J., Ndong Bass I., Mba Djondzo F.A., Djomsi D.M., Kouanfack C., Peeters M., and J. Cappelle. 2023. A Bayesian analysis of birth pulse effects on the probability of detecting Ebola virus in fruit bats. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.10.552777 [2] Caron A., Bourgarel M., Cappelle J., Liégeois F., De Nys H.M., and F. Roger. 2018. Ebola virus maintenance: if not (only) bats, what else? Viruses 10, 549. https://doi.org/10.3390/v10100549 [3] Letko M., Seifert S.N., Olival K.J., Plowright R.K., and V.J. Munster. 2020. Bat-borne virus diversity, spillover and emergence. Nature Reviews Microbiology 18, 461–471. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-0394-z [4] Leroy E.M., Kumulungui B., Pourrut X., Rouquet P., Hassanin A., Yaba P., Délicat A., Paweska J.T., Gonzalez J.P., and R. Swanepoel. 2005. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 438, 575–576. https://doi.org/10.1038/438575a [5] Djomsi D.M. et al. 2022. Dynamics of antibodies to Ebolaviruses in an Eidolon helvum bat colony in Cameroon. Viruses 14, 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14030560 [6] Peel A.J. et al. 2016. Bat trait, genetic and pathogen data from large-scale investigations of African fruit bats Eidolon helvum. Scientific data 3, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.49 [7] Nyandjo Bamen H.L., Ntaganda J.M., Tellier A. and O. Menoukeu Pamen. 2023. Impact of imperfect vaccine, vaccine trade-off and population turnover on infectious disease dynamics. Mathematics, 11(5), p.1240. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11051240 [8] Saadi N., Chi Y.L., Ghosh S., Eggo R.M., McCarthy C.V., Quaife M., Dawa J., Jit M. and A. Vassall. 2021. Models of COVID-19 vaccine prioritisation: a systematic literature search and narrative review. BMC medicine, 19, pp.1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-02190-3 [9] Maerkle, H., John S., Metzger, L., STOP-HCV Consortium, Ansari, M.A., Pedergnana, V. and Tellier, A., 2023. Inference of host-pathogen interaction matrices from genome-wide polymorphism data. bioRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.06.547816. [10] Gandon S., Day T., Metcalf C.J.E. and B.T. Grenfell. 2016. Forecasting epidemiological and evolutionary dynamics of infectious diseases. Trends in ecology & evolution, 31(10), pp.776-788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.07.010 | A Bayesian analysis of birth pulse effects on the probability of detecting Ebola virus in fruit bats | David R.J. Pleydell, Innocent Ndong Bass, Flaubert Auguste Mba Djondzo, Dowbiss Meta Djomsi, Charles Kouanfack, Martine Peeters, Julien Cappelle | <p>Since 1976 various species of Ebolavirus have caused a series of zoonotic outbreaks and public health crises in Africa. Bats have long been hypothesised to function as important hosts for ebolavirus maintenance, however the transmission ecology... |  | Animal diseases, Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecohealth, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Epidemiology, Population dynamics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Reservoirs, Viruses, Zoonoses | Aurelien Tellier | 2023-08-16 16:57:05 | View | |

23 Mar 2023

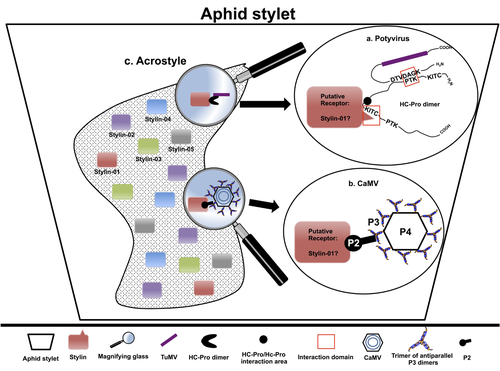

The helper strategy in vector-transmission of plant virusesDi Mattia Jérémy, Zeddam Jean Louis, Uzest Marilyne and Stéphane Blanc https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7709290The intriguing success of helper components in vector-transmission of plant viruses.Recommended by Christine Coustau based on reviews by Jamie Bojko and Olivier SchumppMost plant-infecting viruses rely on an animal vector to be transmitted from one sessile host plant to another. A fascinating aspect of virus-vector interactions is the fact that viruses from different clades produce different proteins to bind vector receptors (1). Two major processes are described. In the “capsid strategy”, a motif of the capsid protein is directly binding to the vector receptor. In the “helper strategy”, a non-structural component, the helper component (HC), establishes a bridge between the virus particle and the vector’s receptor. In this exhaustive review focusing on hemipteran insect vectors, Di Mattia et al. (2) are revisiting the helper strategy in light of recent results. The authors first place the discoveries of the HC strategy in a historical context, suggesting that HC are exclusively found in non-circulative viruses (viruses that only attach to the vector). They present an overview of the nature and modes of action of helper components in the major virus clades of non-circulative viruses (Potyviruses and Caulimoviruses). Authors then detail recent advances, to which they have significantly contributed, showing that the helper strategy also appears widespread in circulative transmission categories (Tenuiviruses, Nanoviruses). In an extensive perspective section, they raise the question of the evolutionary significance of the existence of HC in numerous unrelated viruses, transmitted by unrelated vectors through different mechanisms. They explore the hypothesis that the helper strategy evolved several times independently in distinct viral clades and for different reasons. In particular, they present several potential benefits of plant virus HC related to virus cooperation, collective transmission and effector-driven infectivity. As pointed out by both reviewers, this is a very clear and synthetic review. Di Mattia et al. present an exhaustive overview of virus HC-vector molecular interactions and address functionally and evolutionarily important questions. This review should benefit a large audience interested in host-virus interactions and transmission processes. REFERENCES (1) Ng JCK, Falk BW (2006) Virus-Vector Interactions Mediating Nonpersistent and Semipersistent Transmission of Plant Viruses. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 44, 183–212. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.phyto.44.070505.143325 (2) Di Mattia J, Zeddam J-L, Uzest M, Blanc S (2023) The helper strategy in vector-transmission of plant viruses. Zenodo, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Infections. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7709290 | The helper strategy in vector-transmission of plant viruses | Di Mattia Jérémy, Zeddam Jean Louis, Uzest Marilyne and Stéphane Blanc | <p>An intriguing aspect of vector-transmission of plant viruses is the frequent involvement of a helper component (HC). HCs are virus-encoded non-structural proteins produced in infected plant cells that are mandatory for the transmission success.... |  | Evolution of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Interactions between hosts and infectious agents/vectors, Molecular biology of infections, Molecular genetics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Plant diseases, Vectors, Viruses | Christine Coustau | 2022-10-28 17:32:39 | View | |

21 Jul 2022

Structural variation turnovers and defective genomes: key drivers for the in vitro evolution of the large double-stranded DNA koi herpesvirus (KHV)Nurul Novelia Fuandila, Anne-Sophie Gosselin-Grenet, Marie-Ka Tilak, Sven M Bergmann, Jean-Michel Escoubas, Sandro Klafack, Angela Mariana Lusiastuti, Munti Yuhana, Anna-Sophie Fiston-Lavier, Jean-Christophe Avarre, Emira Cherif https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.10.483410Understanding the in vitro evolution of Cyprinid herpesvirus 3 (CyHV-3), a story of structural variations that can lead to the design of attenuated virus vaccinesRecommended by Jorge Amich based on reviews by Lucie Cappuccio and Veronique Hourdel based on reviews by Lucie Cappuccio and Veronique Hourdel

Structural variations (SVs) play a key role in viral evolution, and therefore they are also important for infection dynamics. However, the contribution of structural variations to the evolution of double-stranded viruses is limited. This knowledge can help to understand the population dynamics and might be crucial for the future development of viral attenuated vaccines. In this study, Fuandila et al (1) use the Cyprinid herpesvirus 3 (CyHV-3), commonly known as koi herpesvirus (KHV), to investigate the variability and contribution of structural variations (SV) for viral evolution after 99 passages in vitro. This virus, with the largest genome among herperviruses, causes a lethal infection in common carp and koi associated with mortalities up to 95% (2). Interestingly, KHV infections are caused by haplotype mixtures, which possibly are a source of genome diversification, but make genomic comparisons more difficult. The authors have used ultra-deep long-read sequencing of two passages, P78 and P99, which were previously described to have differences in virulence. They have found a surprisingly high and wide distribution of SVs along the genome, which were enriched in inversion and deletion events and that often led to defective viral genomes. Although it is known that these defective viral genomes negatively impact viral replication, their implications for virus persistence are still unclear. Subsequently, the authors concentrated on the virulence-relevant region ORF150, which was found to be different in P78 (deletion in 100% of the reads) and P99 (reference-like haplotype). To understand this loss and gain of full ORF150, they searched for SV turn-over in 10 intermediate passages. This analysis revealed that by passage 10 deleted and inverted (attenuated) haplotypes had already appeared, steadily increased frequency until P78, and then completely disappeared between P78 and P99. This is a striking result that raises new questions as to how this clearance occurs, which is really important as these reversions may result in undesirable increases in virulence of live-attenuated vaccines. We recommend this preprint because its use of ultra-deep long-read sequencing has permitted to better understand the role of SV diversity and dynamics in viral evolution. This study shows an unexpectedly high number of structural variations, revealing a novel source of virus diversification and confirming the different mixtures of haplotypes in different passages, including the gain of function. This research provides basic knowledge for the future design of live-attenuated vaccines, to prevent the reversion to virulent viruses. References (1) Fuandila NN, Gosselin-Grenet A-S, Tilak M-K, Bergmann SM, Escoubas J-M, Klafack S, Lusiastuti AM, Yuhana M, Fiston-Lavier A-S, Avarre J-C, Cherif E (2022) Structural variation turnovers and defective genomes: key drivers for the in vitro evolution of the large double-stranded DNA koi herpesvirus (KHV). bioRxiv, 2022.03.10.483410, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.10.483410 (2) Sunarto A, McColl KA, Crane MStJ, Sumiati T, Hyatt AD, Barnes AC, Walker PJ. Isolation and characterization of koi herpesvirus (KHV) from Indonesia: identification of a new genetic lineage. Journal of Fish Diseases, 34, 87-101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2761.2010.01216.x | Structural variation turnovers and defective genomes: key drivers for the in vitro evolution of the large double-stranded DNA koi herpesvirus (KHV) | Nurul Novelia Fuandila, Anne-Sophie Gosselin-Grenet, Marie-Ka Tilak, Sven M Bergmann, Jean-Michel Escoubas, Sandro Klafack, Angela Mariana Lusiastuti, Munti Yuhana, Anna-Sophie Fiston-Lavier, Jean-Christophe Avarre, Emira Cherif | <p style="text-align: justify;">Structural variations (SVs) constitute a significant source of genetic variability in virus genomes. Yet knowledge about SV variability and contribution to the evolutionary process in large double-stranded (ds)DNA v... |  | Animal diseases, Evolution of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Genomics, functional genomics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Viruses | Jorge Amich | Lucie Cappuccio, Veronique Hourdel | 2022-03-11 10:50:50 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Jorge Amich

Christine Chevillon

Fabrice Courtin

Christine Coustau

Thierry De Meeûs

Heather R. Jordan

Karl-Heinz Kogel

Yannick Moret

Thomas Pollet

Benjamin Roche

Benjamin Rosenthal

Bashir Salim

Lucy Weinert