Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * ▼ | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

23 Jan 2023

Whole blood transcriptome profiles of trypanotolerant and trypanosusceptible cattle highlight a differential modulation of metabolism and immune response during infection by Trypanosoma congolenseMoana Peylhard, David Berthier, Guiguigbaza-Kossigan Dayo, Isabelle Chantal, Souleymane Sylla, Sabine Nidelet, Emeric Dubois, Guillaume Martin, Guilhem Sempéré, Laurence Flori, Sophie Thévenon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.10.495622Whole genome transcriptome reveals metabolic and immune susceptibility factors for Trypanosoma congolense infection in West-African livestockRecommended by Concepción Marañón based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersAfrican trypanosomiasis is caused by to the infection of a protozoan parasite of the Trypanosoma genus. It is transmitted by the tsetse fly, and is largely affecting cattle in the sub-humid areas of Africa, causing a high economic impact. However, not all the bovine strains are equally susceptible to the infection (1). In order to dissect the mechanisms underlying susceptibility to African trypanosoma infection, Peylhard et al (2) performed blood transcriptional profiles of trypanotolerant, trypanosensitive and mixed cattle breeds, before and after experimental infection with T. congolense. First of all, the authors have characterized the basal transcriptional profiles in the blood of the different breeds under study, which could be classified in a wide array of functional pathways. Of note, after infection some pathways were consistently enriched in all the group tested. Among them, the immune system-related ones were again on the top functions reported. The search for specific canonical pathways pointed to a prominent role of lipid and cholesterol-related pathways, as well as mitochondrial function and B and T lymphocyte activation. However, the analysis of infected animals demonstrated that trypanosusceptible animals showed a stronger transcriptomic reprogramming, highly enriched in specific metabolic and immunological pathways. It is worthy to highlight striking differences in genes involved in immune signal transduction, cytokines and markers of different leukocyte subpopulations. This work represents undoubtedly a significant momentum in the field, since the authors explore in deep a wide panel of cattle breeds representing the majority of West-African taurine and zebu in a systematic way. Since the animals were studied at different timepoints after infection, future longitudinal analyses of these datasets will be providing a precious insight on the kinetics of immune and metabolic reprogramming associated with susceptibility and tolerance to African trypanosoma infection, widening the application of this interesting study into new therapeutic interventions. References 1. Berthier D, Peylhard M, Dayo G-K, Flori L, Sylla S, Bolly S, Sakande H, Chantal I, Thevenon S (2015) A Comparison of Phenotypic Traits Related to Trypanotolerance in Five West African Cattle Breeds Highlights the Value of Shorthorn Taurine Breeds. PLOS ONE, 10, e0126498. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0126498 2. Peylhard M, Berthier D, Dayo G-K, Chantal I, Sylla S, Nidelet S, Dubois E, Martin G, Sempéré G, Flori L, Thévenon S (2022) Whole blood transcriptome profiles of trypanotolerant and trypanosusceptible cattle highlight a differential modulation of metabolism and immune response during infection by Trypanosoma congolense. bioRxiv, 2022.06.10.495622, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.10.495622. | Whole blood transcriptome profiles of trypanotolerant and trypanosusceptible cattle highlight a differential modulation of metabolism and immune response during infection by Trypanosoma congolense | Moana Peylhard, David Berthier, Guiguigbaza-Kossigan Dayo, Isabelle Chantal, Souleymane Sylla, Sabine Nidelet, Emeric Dubois, Guillaume Martin, Guilhem Sempéré, Laurence Flori, Sophie Thévenon | <p>Animal African trypanosomosis, caused by blood protozoan parasites transmitted mainly by tsetse flies, represents a major constraint for millions of cattle in sub-Saharan Africa. Exposed cattle include trypanosusceptible indicine breeds, severe... |  | Animal diseases, Genomics, functional genomics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Resistance/Virulence/Tolerance | Concepción Marañón | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2022-06-14 17:06:57 | View |

08 Aug 2023

A global Corynebacterium diphtheriae genomic framework sheds light on current diphtheria reemergenceMelanie Hennart, Chiara Crestani, Sebastien Bridel, Nathalie Armatys, Sylvie Brémont, Annick Carmi-Leroy, Annie Landier, Virginie Passet, Laure Fonteneau, Sophie Vaux, Julie Toubiana, Edgar Badell, Sylvain Brisse https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.20.529124DIPHTOSCAN : A new tool for the genomic surveillance of diphtheriaRecommended by Rodolfo García-Contreras based on reviews by Ankur Mutreja and 2 anonymous reviewersOne of the greatest achievements of health sciences is the eradication of infectious diseases such as smallpox that in the past imposed a severe burden on humankind, through global vaccination campaigns. Moreover, progress towards the eradication of others such as poliomyelitis, dracunculiasis, and yaws is being made. In contrast, other infections that were previously contained are reemerging, due to several factors, including lack of access to vaccines due to geopolitical reasons, the rise of anti-vaccine movements, and the constant mobility of infected persons from the endemic sites. One of such disease is diphtheria, caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae and a few other related species such as C. ulcerans and C. pseudotuberculosis. Importantly, in France, diphtheria cases reported in 2022 increased 7-fold from the average of previously recorded cases per year in the previous 4 years and the situation in other European countries is similar. Hence, as reported here, Hennart et al. (2023) developed DIPHTOSCAN, a free access bioinformatics tool with user-friendly interphase, aimed to easily identify, extract and interpret important genomic features such as the sublineage of the strain, the presence of the tox gene (as a string predictor for toxigenic disease) as well as genes coding other virulence factors such as fimbriae, and the presence of know resistant mechanisms towards antibiotics like penicillin and erythromycin currently used in the clinic to treat this infection. The authors validated the performance of their tool with a large collection of genomes, including those obtained from the isolates of the 2022 outbreak in France, more than 1,200 other genomes isolated from France, Algeria, and Yemen, and more than 500 genomes from several countries from Europe, America, Africa, Asia, and Oceania that are available through the NCBI site. DIPHTOSCAN will allow the rapid identification and surveillance of potentially dangerous strains such as those being tox-positive isolates and resistant to multiple drugs and/or first-line treatments and a better understanding of the epidemiology and evolution of this important reemerging disease. | A global *Corynebacterium diphtheriae* genomic framework sheds light on current diphtheria reemergence | Melanie Hennart, Chiara Crestani, Sebastien Bridel, Nathalie Armatys, Sylvie Brémont, Annick Carmi-Leroy, Annie Landier, Virginie Passet, Laure Fonteneau, Sophie Vaux, Julie Toubiana, Edgar Badell, Sylvain Brisse | <p style="text-align: justify;"><strong>Background</strong></p> <p style="text-align: justify;">Diphtheria, caused by <em>Corynebacterium diphtheriae</em>, reemerges in Europe since 2022. Genomic sequencing can inform on transmission routes and g... | Drug resistance, tolerance and persistence, Epidemiology, Evolution of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Genomics, functional genomics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Microbiology of infections, Population genetics of hosts, infectiou... | Rodolfo García-Contreras | Ankur Mutreja | 2023-03-09 16:02:27 | View | |

27 Feb 2023

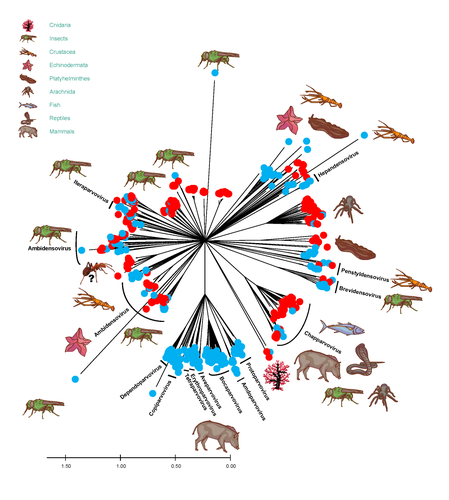

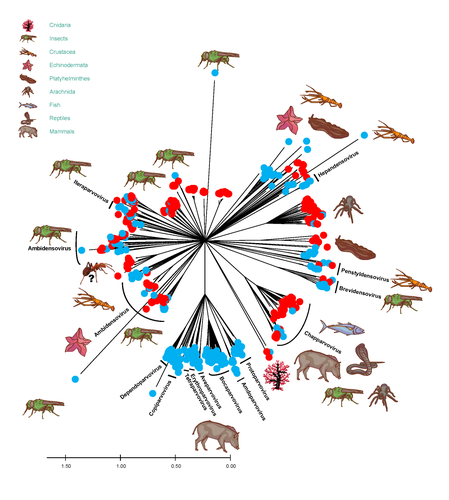

African army ants at the forefront of virome surveillance in a remote tropical forestMatthieu Fritz, Berenice Reggiardo, Denis Filloux, Lisa Claude, Emmanuel Fernandez, Frederic Mahe, Simona Kraberger, Joy M. Custer, Pierre Becquart, Telstar Ndong Mebaley, Linda Bohou Kombila, Leadisaelle H. Lenguiya, Larson Boundenga, Illich M. Mombo, Gael Darren Maganga, Fabien R. Niama, Jean-Sylvain Koumba, Mylene Ogliastro, Michel Yvon, Darren Martin, Stephane Blanc, Arvind Varsani, Eric Leroy, Philippe Roumagnac https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.13.520061A groundbreaking study using ants revealed a spectacular diversity of viruses in hardly accessible ecosystems like tropical forestsRecommended by Sebastien Massart based on reviews by Mart Krupovic and 1 anonymous reviewerDeciphering the virome (the set or assemblage of viruses) of the Earth, from individual organisms to entire ecosystems, has become a key priority. The first step to better understanding the impact of viruses on the ecology and functions of ecosystems is to describe their diversity. Such knowledge opens the gates to a better assessment of global nutrient cycling or of the threat that viruses represent to individual health. This explains the increasing number of pioneering studies that are currently sequencing the complete or partial genome of thousands of new viruses [1]. In their exciting study, Fritz and collaborators [2], authors sampled 209 army ants (Genus Dorylus) to investigate the virus diversity in dense forests that researchers cannot easily access. Indeed, these ants live in colonies (21 were sampled) that can move 1 km per day, covering a significant area and attacking many invertebrate and vertebrate preys. Each sample was sequenced by a protocol called VANA sequencing and allowing the enrichment of the sample in viral sequences [3], so improving the detection of viruses present at low abundance in the ant (and more specifically in its gut for viruses infecting preys). Around 45,000 contigs presented homologies with bacterial, plant, invertebrate, and vertebrate infecting viruses. Half could be assigned to 56 families and 157 genera of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Beyond this amazing harvest of new and known virus sequences using an original methodology, the results significantly improve the current frontiers of known viral taxonomy and diversity and raise exciting research tracks to expand them. As a preprint, several blogs or news of leading scientists and journals have already highlighted this study. For example, in the news section of Science magazine, Jon Cohen underlined the originality of the approach for virus hunting on Earth with the title “Armed with air samplers, rope tricks, and—yes—ants, virus hunters spot threats in new ways”[4]. Another example is the mention of the publication by Elisabeth Bik in her Microbiome Digest: she wrote, “An amazing read is a fresh preprint from Fritz and collaborator describing an exciting method of sampling in difficult-to-reach environments“ [5]. The paper from Fritz et al [2] thus represents a significant advance in virus ecology, as already recognized by early readers, and this is why I strongly recommend its publication in PCI Infections. REFERENCES 1. Edgar RC, Taylor J, Lin V, Altman T, Barbera P, Meleshko D, Lohr D, Novakovsky G, Buchfink B, Al-Shayeb B, Banfield JF, de la Peña M, Korobeynikov A, Chikhi R, Babaian A (2022) Petabase-scale sequence alignment catalyses viral discovery. Nature, 602, 142–147. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04332-2 2. Fritz M, Reggiardo B, Filloux D, Claude L, Fernandez E, Mahé F, Kraberger S, Custer JM, Becquart P, Mebaley TN, Kombila LB, Lenguiya LH, Boundenga L, Mombo IM, Maganga GD, Niama FR, Koumba J-S, Ogliastro M, Yvon M, Martin DP, Blanc S, Varsani A, Leroy E, Roumagnac P (2023) African army ants at the forefront of virome surveillance in a remote tropical forest. bioRxiv, 2022.12.13.520061, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.13.520061 3. François S, Filloux D, Fernandez E, Ogliastro M, Roumagnac P (2018) Viral Metagenomics Approaches for High-Resolution Screening of Multiplexed Arthropod and Plant Viral Communities. In: Viral Metagenomics: Methods and Protocols Methods in Molecular Biology. (eds Pantaleo V, Chiumenti M), pp. 77–95. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7683-6_7 4. Cohen J (2023) Virus hunters test new surveillance tools. Science, 379, 16–17. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg5292 5. Ponsero A (2023) February 18th, 2023. Microbiome Digest - Bik’s Picks. https://microbiomedigest.com/2023/02/18/february-18th-2023/ | African army ants at the forefront of virome surveillance in a remote tropical forest | Matthieu Fritz, Berenice Reggiardo, Denis Filloux, Lisa Claude, Emmanuel Fernandez, Frederic Mahe, Simona Kraberger, Joy M. Custer, Pierre Becquart, Telstar Ndong Mebaley, Linda Bohou Kombila, Leadisaelle H. Lenguiya, Larson Boundenga, Illich M. M... | <p style="text-align: justify;">In this study, we used a predator-enabled metagenomics strategy to sample the virome of a remote and difficult-to-access densely forested African tropical region. Specifically, we focused our study on the use of arm... |  | Ecohealth, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, One Health, Reservoirs, Viruses | Sebastien Massart | 2022-12-14 11:57:40 | View | |

16 Jul 2024

Diverse fox circovirus (Circovirus canine) variants circulate at high prevalence in grey wolves (Canis lupus) from the Northwest Territories, CanadaMarta Canuti, Abigail V.L. King, Giovanni Franzo, H. Dean Cluff, Lars E. Larsen, Heather Fenton, Suzanne C. Dufour, Andrew S. Lang https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.08.584028Wild canine viruses in the news. Better understanding multi-host transmission by adopting a disease ecology species community-based approachRecommended by Jean-Francois Guégan based on reviews by Arvind Varsani and 1 anonymous reviewerAccording to the international animal health authority, i.e., the World Organization on Animal Health (WOAH, former OIE), circoviruses are part of the Circoviridae family, which only includes 2 genera Circovirus and Cyclovirus, and infect swine, canine, ursid, viverrid, felid, pinniped, herpestid, mustelid, and several avian species (WOAH 2021). They are small (12–27 nm), non-enveloped, circular, single-stranded DNA viruses, viral replication is nuclear, and wild and domestic birds and mammals could serve as natural hosts. If most infections caused by circoviruses are subclinical in both wild and domestic species, they can be responsible for severe diseases in the commercial pig industry due to the Porcine circovirus-2 (PCV-2). These viruses can constitute a threat to wildlife, and cause their hosts to become immunocompromised, and animals often present with secondary coinfections. Canine circoviruses (CanineCV) harbour a worldwide distribution in dogs, and is the sole member of the viral genus to infect canines. They can be detected in wild carnivores, such as wolves, badgers, foxes and jackals, which indicates an ability for cross-species transmission between wildlife and domestic dogs. However, fox circovirus (FoCV), a distinct lineage of CanineCV, has been identified exclusively in wild canids (foxes and wolves) and not in dogs in Europe and North America, where it can cause in red foxes meningoencephalitis and other central nervous system signs. In their article, Canuti et al. (2024) investigate the presence, distribution and ecology of CanineCV in grey wolf specimens from the Northwest Territories, Canada. CanineCV occurrence appears to be relatively high with 45.3% positive specimens and parvoviral superinfections observed. The authors identify a high CanineCV genetic diversity among the investigated grey wolf specimens, and exacerbated by viral recombination. Phylogenetic analysis reveals the existence of 4 lineages, within each of them strains segregate by geography and not by host origin. This observed geographic segregation is interpreted as being due to the absence of exchange flows between grey wolf host subpopulations. Due to the paucity of knowledge on these circoviruses in wildlife and at the interface between wild and domestic animals, the authors discuss the plausible role of wolves as natural host reservoirs for disease transmission due to long-lasting virus-host coevolution. They are also conscious that additional maintenance hosts could exist in the wild, claiming for further studies to decipher fox circovirus disease ecology and transmission dynamics. This study underlines the importance of better understanding the transmission ecology and evolution of these Canine circoviruses, and I can only agree. Xiao et al. (2023), a research not referred to in the present work, evidenced CanineCV infection in cats in China, and obtained the first whole genome of cat-derived CanineCV. This emphasizes the importance of monitoring additional animal species and locations in the world to clarify disease ecology and transmission dynamics. A broader sampling of a wide range of animal species in different parts of the world using a species community-based approach is the key to understanding these CanineCV infections. References Marta CANUTI, Abigail V.L. KING, Giovanni FRANZO, H. Dean CLUFF, Lars E. LARSEN, Heather FENTON, Suzanne C. DUFOUR, Andrew S. LANG. 2024. Diverse fox circovirus (Circovirus canine) variants circulate at high prevalence in grey wolves (Canis lupus) from the Northwest Territories, Canada. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.08.584028 World Organization on Animal Health. 2021. Circoviruses. https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2021/05/circoviruses-infection-with.pdf [consulted on July 9th, 2024]. Xiangyu XIAO, Yan CHAO LI, Feng PEI XU, Xiangpi HAO, Shoujun LI, Pei ZHOU. 2023. Canine circovirus among dogs and cats in China: first identification in cats. Front. Microbiol. 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1252272 | Diverse fox circovirus (*Circovirus canine*) variants circulate at high prevalence in grey wolves (*Canis lupus*) from the Northwest Territories, Canada | Marta Canuti, Abigail V.L. King, Giovanni Franzo, H. Dean Cluff, Lars E. Larsen, Heather Fenton, Suzanne C. Dufour, Andrew S. Lang | <p style="text-align: justify;">Canine circoviruses (CanineCV) have a worldwide distribution in dogs and are occasionally detected in wild carnivorans, indicating their ability for cross-species transmission. However, fox circovirus, a lineage of ... | Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Epidemiology, Molecular genetics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Population genetics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Reservoirs, Taxonomy of hosts, infec... | Jean-Francois Guégan | Martine Peeters, Arvind Varsani | 2024-03-09 09:04:29 | View | |

07 Feb 2023

Three-way relationships between gut microbiota, helminth assemblages and bacterial infections in wild rodent populationsMarie Bouilloud, Maxime Galan, Adelaide Dubois, Christophe Diagne, Philippe Marianneau, Benjamin Roche, Nathalie Charbonnel https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.23.493084Unveiling the complex interactions between members of gut microbiomes: a significant advance provided by an exhaustive study of wild bank volesRecommended by Thomas Pollet based on reviews by Jason Anders and 1 anonymous reviewerThe gut of vertebrates is a host for hundreds or thousands of different species of microorganisms named the gut microbiome. This latter may differ greatly in natural environments between individuals, populations and species (1). The vertebrate gut microbiome plays key roles in host fitness through functions including nutrient acquisition, immunity and defense against infectious agents. While bank voles are small mammals potentially reservoirs of a large number of infectious agents, questions about the links between their gut microbiome and the presence of pathogens are scarcely addressed. In this study, Bouilloud et al. (2) used complementary analyses of community and microbial ecology to (i) assess the variability of gut bacteriome diversity and composition in wild populations of the bank vole Myodes glareolus collected in four different sites in Eastern France and (ii) evaluate the three-way interactions between the gut bacteriota, the gastro-intestinal helminths and pathogenic bacteria detected in the spleen. Authors identified important variations of the gut bacteriota composition and diversity among bank voles mainly explained by sampling localities. They found positive correlations between the specific richness of both the gut bacteria and the helminth community, as well as between the composition of these two communities, even when accounting for the influence of geographical distance. The helminths Aonchotheca murissylvatici, Heligmosomum mixtum and the bacteria Bartonella sp were the main taxa associated with the whole gut bacteria composition. Besides, changes in relative abundance of particular gut bacterial taxa were specifically associated with other helminths (Mastophorus muris, Catenotaenia henttoneni, Paranoplocephala omphalodes and Trichuris arvicolae) or pathogenic bacteria. Infections with Neoehrlichia mikurensis, Orientia sp, Rickettsia sp and P. omphalodes were especially associated with lower relative abundance of members of the family Erysipelotrichaceae (Firmicutes), while coinfections with higher number of bacterial infections were associated with lower relative abundance of members of the Bacteroidales family (Bacteroidetes). As pointed out by both reviewers, this study represents a significant advance in the field. I would like to commend the authors for this enormous work. The amount of data, analyses and results is considerable which has sometimes complicated the understanding of the story at the beginning of the evaluation process. Thanks to constructive scientific interactions with both reviewers through the two rounds of evaluation, the authors have efficiently addressed the reviewer's concerns and improved the manuscript, making this great story easier to read. The innovative results of this study emphasize the complex interlinkages between gut bacteriome and infections in wild animal populations and I strongly recommend this article for publication In Peer Community Infections. References (1) Vujkovic-Cvijin I, Sklar J, Jiang L, Natarajan L, Knight R, Belkaid Y (2020) Host variables confound gut microbiota studies of human disease. Nature, 587, 448–454. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2881-9 (2) Bouilloud M, Galan M, Dubois A, Diagne C, Marianneau P, Roche B, Charbonnel N (2023) Three-way relationships between gut microbiota, helminth assemblages and bacterial infections in wild rodent populations. biorxiv, 2022.05.23.493084, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.23.493084 | Three-way relationships between gut microbiota, helminth assemblages and bacterial infections in wild rodent populations | Marie Bouilloud, Maxime Galan, Adelaide Dubois, Christophe Diagne, Philippe Marianneau, Benjamin Roche, Nathalie Charbonnel | <p>Background</p> <p>Despite its central role in host fitness, the gut microbiota may differ greatly between individuals. This variability is often mediated by environmental or host factors such as diet, genetics, and infections. Recently, a part... | Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecohealth, Interactions between hosts and infectious agents/vectors, Reservoirs, Zoonoses | Thomas Pollet | 2022-05-25 10:13:23 | View | ||

28 May 2024

HIV self-testing positivity rate and linkage to confirmatory testing and care: a telephone survey in Côte d'Ivoire, Mali and SenegalKra Djuhe Arsene Kouassi, Arlette Simo Fotso, Nicolas Rouveau, Mathieu Maheu-Giroux, Marie-Claude Boily, Romain Silhol, Marc d'Elbee, Anthony Vautier, Joseph Larmarange, ATLAS Team https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.10.23291206The benefits of HIV self-testing in West Africa: quantified.Recommended by Jessie Abbate based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersDespite decades of advances and understanding of the indiscriminate nature of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), it remains shrouded in stigma that makes it difficult to reach some key populations at risk of transmission. The advent of self-testing technology for HIV (HIVST) has opened much-needed potential for bringing privacy to prevention that is crucial for curtailing its continued spread (Johnson et al., 2014). The HIV Self-Testing in Africa (STAR) Initiative (https://www.psi.org/fr/project/star/), carried out in Eastern and Southern Africa between 2015 and 2020 (Simwinga et al., 2022), demonstrated the market and public health operational potential of HIVST of different distribution methods. From 2019 to 2022, the “AutoTest de dépistage du VIH : Libre d’Accéder à la connaissance de son Statut" (ATLAS, translating to “HIVST: Freedom to know your status”) program built on these findings to quantify the public health value of HIVST for reaching key populations in West Africa (specifically, Mali, Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire) (Ky-Zerbo et al., 2022). The innovative secondary distribution methods these studies employed, where the primary targeted populations were also encouraged to take and provide tests to their contacts, helped widen the reach of HIVST within key population networks beyond those relying on access to HIV testing facilities.

The tricky part of the self-testing model lies in assessing its reach and impact while maintaining the privacy of self-testers that is central to its success. Following voluntary phone survey methods that previously were able to show expanded reach of HIVST to first-time testers in key populations in West Africa and high rates of confirmatory testing and treatment seeking (Kra et al., 2022), Kra et al. (Kra et al., 2024) quantified how many of these self-tests led to a positive result – allowing wider assessment of follow-up behaviors and positivity rates among the hard-to-reach populations the program had targeted.

While the numbers were low, the results were informative. Among respondents who reported a positive (“reactive”) HIVST, just 44% proceeded to confirmatory testing. This is lower than in other populations where HIVST follow-up has been assessed (Thirumurthy et al., 2016). The main reasons given for not confirming a reactive self-test was misinterpretation of HIVST results and not understanding that confirmatory testing was needed. The result thus highlighted a need for improved communication on how to correctly interpret HIVST results, and the authors provided ranges for how this misinterpretation could have affected their positivity estimates. However, the majority of those who sought confirmatory testing did so within 3 months, and nearly all of those with confirmed infection started on treatment. HIV positivity rates in the three countries were all higher than other published HIV positivity estimates (Giguère et al., 2021; Maheu-Giroux et al., 2019), suggesting that HIVST methods were highly effective at reaching the targeted communities. Finally, while the authors demonstrated their methods as an effective way of assessing the utility of HIVST campaigns and identifying ways to improve them, the follow-up surveys are likely too costly to replace current passive surveillance methods for assessing community disease burden. That said, these precious data should be taken as validation of the public health value of HIV self-testing in key populations across communities in West Africa. With improvements in communicating instructions for use and follow-up, there is little doubt that the innovation of HIVST primary and secondary distribution could become a widely useful addition to the fight against HIV.

References Giguère, K., Eaton, J. W., Marsh, K., Johnson, L. F., Johnson, C. C., Ehui, E., Jahn, A., Wanyeki, I., Mbofana, F., Bakiono, F., Mahy, M., & Maheu-Giroux, M. (2021). Trends in knowledge of HIV status and efficiency of HIV testing services in sub-Saharan Africa, 2000–20: a modelling study using survey and HIV testing programme data. The Lancet HIV, 8(5), e284–e293. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30315-5 Johnson, C., Baggaley, R., Forsythe, S., Van Rooyen, H., Ford, N., Napierala Mavedzenge, S., Corbett, E., Natarajan, P., & Taegtmeyer, M. (2014). Realizing the potential for HIV self-testing. In AIDS and Behavior (Vol. 18, Issue SUPPL. 4). Springer New York LLC. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0832-x Kra, A. K., Fosto, A. S., N’guessan, K. N., Geoffroy, O., Younoussa, S., Kabemba, O. K., Gueye, P. A., Ndeye, P. D., Rouveau, N., Boily, M. C., Silhol, R., d’Elbée, M., Maheu-Giroux, M., Vautier, A., & Larmarange, J. (2022). Can HIV self-testing reach first-time testers? A telephone survey among self-test end users in Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, and Senegal. BMC Infectious Diseases, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08626-w Kra, A. K., Fotso, A. S., Rouveau, N., Maheu-Giroux, M., Boily, M.-C., Silhol, R., d’Elbée, M., Vautier, A., Lamarange, J., & the Atlas team. (2024). HIV self-testing positivity rate and linkage to confirmatory testing and care: a telephone survey in Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, and Senegal. MedRxiv, Ver. 4 Peer-Reviewed and Recommended by Peer Community in Infections, 2023.06.10.23291206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.10.23291206 Ky-Zerbo, O., Desclaux, A., Boye, S., Maheu-Giroux, M., Rouveau, N., Vautier, A., Camara, C. S., Kouadio, B. A., Sow, S., Doumenc-Aidara, C., Gueye, P. A., Geoffroy, O., Kamemba, O. K., Ehui, E., Ndour, C. T., Keita, A., & Larmarange, J. (2022). “I take it and give it to my partners who will give it to their partners”: Secondary distribution of HIV self-tests by key populations in Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, and Senegal. BMC Infectious Diseases, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08319-4 Maheu-Giroux, M., Marsh, K., Doyle, C. M., Godin, A., Lanièce Delaunay, C., Johnson, L. F., Jahn, A., Abo, K., Mbofana, F., Boily, M. C., Buckeridge, D. L., Hankins, C. A., & Eaton, J. W. (2019). National HIV testing and diagnosis coverage in sub-Saharan Africa: A new modeling tool for estimating the “first 90” from program and survey data. AIDS, 33, S255–S269. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002386 Simwinga, M., Gwanu, L., Hensen, B., Sigande, L., Mainga, M., Phiri, T., Mwanza, E., Kabumbu, M., Mulubwa, C., Mwenge, L., Bwalya, C., Kumwenda, M., Mubanga, E., Mee, P., Johnson, C. C., Corbett, E. L., Hatzold, K., Neuman, M., Ayles, H., & Taegtmeyer, M. (2022). Lessons learned from implementation of four HIV self-testing (HIVST) distribution models in Zambia: applying the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to understand impact of contextual factors on implementation. BMC Infectious Diseases, 22(Suppl 1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09168-5 Thirumurthy, H., Masters, S. H., Mavedzenge, S. N., Maman, S., Omanga, E., & Agot, K. (2016). Promoting male partner HIV testing and safer sexual decision making through secondary distribution of self-tests by HIV-negative female sex workers and women receiving antenatal and post-partum care in Kenya: a cohort study. The Lancet HIV, 3(6), e266–e274. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(16)00041-2

| HIV self-testing positivity rate and linkage to confirmatory testing and care: a telephone survey in Côte d'Ivoire, Mali and Senegal | Kra Djuhe Arsene Kouassi, Arlette Simo Fotso, Nicolas Rouveau, Mathieu Maheu-Giroux, Marie-Claude Boily, Romain Silhol, Marc d'Elbee, Anthony Vautier, Joseph Larmarange, ATLAS Team | <p>HIV self-testing (HIVST) empowers individuals to decide when and where to test and with whom to share their results. From 2019 to 2022, the ATLAS program distributed ~ 400 000 HIVST kits in Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, and Senegal. It prioritised key p... |  | Epidemiology | Jessie Abbate | 2023-06-16 16:40:51 | View | |

25 Apr 2023

The distribution, phenology, host range and pathogen prevalence of Ixodes ricinus in France: a systematic map and narrative reviewGrégoire Perez, Laure Bournez, Nathalie Boulanger, Johanna Fite, Barbara Livoreil, Karen D. McCoy, Elsa Quillery, Magalie René-Martellet, and Sarah I. Bonnet https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.18.537315An extensive review of Ixodes ricinus in European FranceRecommended by Ana Sofia Santos based on reviews by Ana Palomar and 1 anonymous reviewerTicks are obligate, bloodsucking, nonpermanent ectoparasitic arthropods. Among them, Ixodes ricinus is a classic example of an extreme generalist tick, presenting a highly permissive feeding behavior using different groups of vertebrates as hosts, such as mammalian (including humans), avian and reptilian species (Hoogstraal & Aeschlimann, 1982; Dantas-Torresa & Otranto, 2013). This ecological adaptation can account for the broad geographical distribution of I. ricinus populations, which extends from the western end of the European continent to the Ural Mountains in Russia, and from northern Norway to the Mediterranean basin, including the North African countries - Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia (https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/disease-vectors/surveillance-and-disease-data/tick-maps). The contact with different hosts also promotes the exposure/acquisition and transmission of various pathogenic agents (viruses, bacteriae, protists and nematodes) of veterinary and medical relevance (Aeschlimann et al., 1979). As one of the prime ticks found on humans, this species is implicated in diseases such as Lyme borreliosis, Spotted Fever Group rickettsiosis, Human Anaplasmosis, Human Babesiosis and Tick-borne Encephalitis (Velez et al., 2023). The climate change projections drawn for I. ricinus, in the scenario of global warming, point for the expansion/increase activity in both latitude and altitude (Medlock et al., 2013). The adequacy of vector modeling is relaying in the proper characterization of complex biological systems. Thus, it is essential to increase knowledge on I. ricinus, focusing on aspects such as genetic background, ecology and eco-epidemiology on a microscale but also at a country and region level, due to possible local adaptations of tick populations and genetic drift. In the present systematic revision, Perez et al. (2023) combine old and recently published data (mostly up to 2020) regarding I. ricinus distribution, phenology, host range and pathogen association in continental France and Corsica Island. Based on a keyword search of peer-reviewed papers on seven databases, as well as other sources of grey literature (mostly, thesis), the authors have synthesized information on: 1) Host parasitism to detect potential differences in host use comparing to other areas in Europe; 2) The spatiotemporal distribution of I. ricinus, to identify possible geographic trends in tick density, variation in activity patterns and the influence of environmental factors; 3) Tick-borne pathogens detected in this species, to better assess their spatial distribution and variation in exposure risk. As pointed out by both reviewers, this work clearly summarizes the information regarding I. ricinus and associated microorganisms from European France. This review also identifies remaining knowledge gaps, providing a comparable basis to orient future research. This is why I chose to recommend Perez et al (2023)'s preprint for Peer Community Infections. REFERENCES Aeschlimann, A., Burgdorfer, W., Matile, H., Peter, O., Wyler, R. (1979) Aspects nouveaux du rôle de vecteur joué par Ixodes ricinus L. en Suisse. Acta Tropica, 36, 181-191. Dantas-Torresa, F., Otranto, D. (2013) Seasonal dynamics of Ixodes ricinus on ground level and higher vegetation in a preserved wooded area in southern Europe. Veterinary Parasitology, 192, 253- 258. Hoogstraal, H., Aeschlimann, A. (1982) Tick-host specificity. Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen Entomologischen Gesellschaft, 55, 5-32. Medlock, J.M., Hansford, K.M., Bormane, A., Derdakova, M., Estrada-Peña, A., George, J.C., Golovljova, I., Jaenson, T.G.T., Jensen, J.K., Jensen, P.M., Kazimirova, M., Oteo, J.A., Papa, A., Pfister, K., Plantard, O., Randolph, S.E., Rizzoli, A., Santos-Silva, M.M., Sprong, H., Vial, L., Hendrickx, G., Zeller, H., Van Bortel, W. (2013) Driving forces for changes in geographical distribution of Ixodes ricinus ticks in Europe. Parasites and Vectors, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-6-1 Perez, G., Bournez, L., Boulanger, N., Fite, J., Livoreil, B., McCoy, K., Quillery, E., René-Martellet, M., Bonnet, S. (2023) The distribution, phenology, host range and pathogen prevalence of Ixodes ricinus in France: a systematic map and narrative review. bioRxiv, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.18.537315 Velez, R., De Meeûs, T., Beati, L., Younsi, H., Zhioua, E., Antunes, S., Domingos, A., Ataíde Sampaio, D., Carpinteiro, D., Moerbeck, L., Estrada-Peña, A., Santos-Silva, M.M., Santos, A.S. (2023) Development and testing of microsatellite loci for the study of population genetics of Ixodes ricinus Linnaeus, 1758 and Ixodes inopinatus Estrada-Peña, Nava & Petney, 2014 (Acari: Ixodidae) in the western Mediterranean region. Acarologia, 63, 356-372. https://doi.org/10.24349/bvem-4h49 | The distribution, phenology, host range and pathogen prevalence of *Ixodes ricinus* in France: a systematic map and narrative review | Grégoire Perez, Laure Bournez, Nathalie Boulanger, Johanna Fite, Barbara Livoreil, Karen D. McCoy, Elsa Quillery, Magalie René-Martellet, and Sarah I. Bonnet | <p style="text-align: justify;">The tick <em>Ixodes ricinus</em> is the most important vector species of infectious diseases in European France. Understanding its distribution, phenology, and host species use, along with the distribution and preva... |  | Animal diseases, Behaviour of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecohealth, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Epidemiology, Geography of infectious diseases, Interactions between hosts and infectious ag... | Ana Sofia Santos | 2022-12-06 14:52:44 | View | |

08 Dec 2022

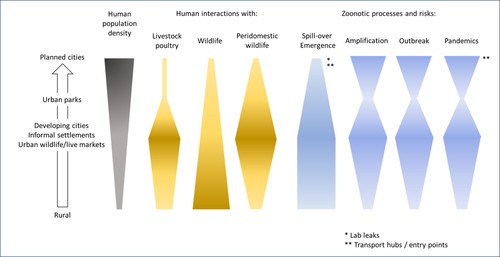

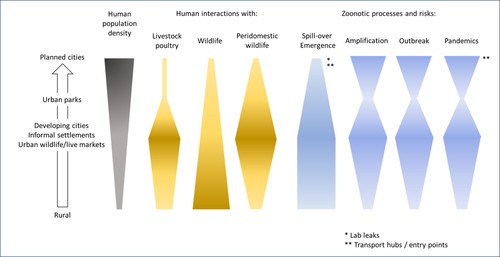

Zoonotic emergence at the animal-environment-human interface: the forgotten urban socio-ecosystemsDobigny, G. & Morand, S. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6444776Zoonotic emergence and the overlooked case of citiesRecommended by Etienne Waleckx based on reviews by Eric Dumonteil, Nicole L. Gottdenker and 1 anonymous reviewerZoonotic pathogens, those transmitted from animals to humans, constitute a major public health risk with high associated global economic costs. Diseases associated with these pathogens represent more than 60% of emerging infectious diseases and predominantly originate in wildlife (1). Over the last decades, the emergence and re-emergence of zoonotic pathogens have led to an increasing number of epidemics, as illustrated by the current Covid-19 pandemic. There is ample evidence that human impact on native ecosystems such as deforestation, agricultural development, and urbanization, is linked to spillover of pathogens from animals to humans (2). However, research and calls to action have mainly focused on the importance of surveillance and prevention of zoonotic emergences along landscape interfaces, with special emphasis on tropical forests and agroecosystems, and studies and reviews pointing out the zoonotic risk associated with cities are scarce. Additionally, cities are sometimes wrongly seen as one homogeneous ecosystem, almost exclusively human, with a Northern hemisphere-biased perception of what a city is, which fails to take into account the ecological and socio-economic diversities that can constitute an urban area. Here, Dobigny and Morand (3) aim to draw attention to the importance of urban ecosystems in zoonotic risk and advocate that further attention should be paid to urban, peri-urban and suburban areas. In this well-organized and well-documented review, the authors show, using updated literature, that cities are places where massive contacts occur between wildlife, domestic animals, and human inhabitants (thus constituting spillover opportunities), and that it is even likely that human and wildlife contact in urban centers is more prevalent than in wild areas, perhaps contrary to intuition. Indeed, cities currently constitute the most important environment of human life and are places for millions of close interactions between humans and animals, including pets and domestic animals, wild animals through the intrusion of wild urban-adapted species (e.g., some bat, rodent, or bird species among others), manipulation and consumption of wildlife meat, and the existence of wildlife meat markets, which all constitute a major risk for zoonotic spillover. In cities, lab escapees of zoonotic pathogens also exist, and trends of adaptation to urban ecological conditions of many vectors of primary health importance is also a concern. The authors further argue that cities are predominant places for both epidemic amplification of human-human transmitted pathogens, because they are places with high human densities and population growth, and for dissemination of reservoirs, vectors and pathogens, as they are transport hubs. Dobigny & Morand further predict, likely correctly, that cities may be important places for pathogen evolution. Finally, they propose actions and recommendations to limit the risk of zoonotic spillover events from urban ecosystems and future directions for research aiming at assessing this risk. The reviewers found the manuscript well-organized and presented, timely, and bringing novel contributions to the field of zoonotic emergence. I strongly recommend this article, which should benefit a large audience, particularly in the context of the current Covid-19 pandemics and the ongoing One Health initiatives aiming at preventing future zoonotic disease emergence (4). References (1) Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, Daszak P (2008) Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature, 451, 990–993. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06536 (2) White RJ, Razgour O (2020) Emerging zoonotic diseases originating in mammals: a systematic review of effects of anthropogenic land-use change. Mammal Review, 50, 336–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/mam.12201 (3) Dobigny G, Morand S (2022) Zoonotic emergence at the animal-environment-human interface: the forgotten urban socio-ecosystems. Zenodo, 6444776, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6444776 (4) Morand S, Lajaunie C (2021) Biodiversity and COVID-19: A report and a long road ahead to avoid another pandemic. One Earth, 4, 920–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.06.007 | Zoonotic emergence at the animal-environment-human interface: the forgotten urban socio-ecosystems | Dobigny, G. & Morand, S. | <p style="text-align: justify;">Zoonotic emergence requires spillover from animals to humans, hence animal-human interactions. A lot has been emphasized on human intrusion into wild habitats (e.g., deforestation, hunting) and the development of ag... |  | Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecohealth, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Evolution of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, One Health, Zoonoses | Etienne Waleckx | 2022-04-11 11:39:11 | View | |

23 Mar 2023

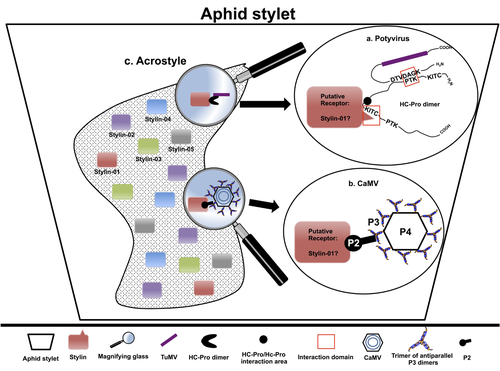

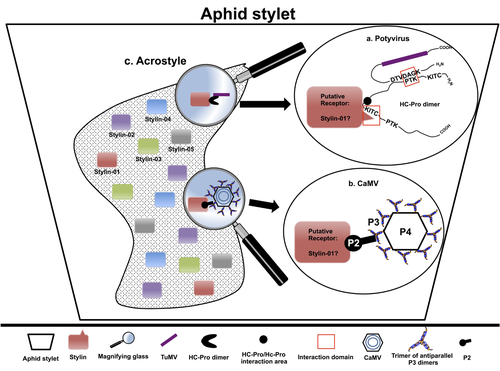

The helper strategy in vector-transmission of plant virusesDi Mattia Jérémy, Zeddam Jean Louis, Uzest Marilyne and Stéphane Blanc https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7709290The intriguing success of helper components in vector-transmission of plant viruses.Recommended by Christine Coustau based on reviews by Jamie Bojko and Olivier SchumppMost plant-infecting viruses rely on an animal vector to be transmitted from one sessile host plant to another. A fascinating aspect of virus-vector interactions is the fact that viruses from different clades produce different proteins to bind vector receptors (1). Two major processes are described. In the “capsid strategy”, a motif of the capsid protein is directly binding to the vector receptor. In the “helper strategy”, a non-structural component, the helper component (HC), establishes a bridge between the virus particle and the vector’s receptor. In this exhaustive review focusing on hemipteran insect vectors, Di Mattia et al. (2) are revisiting the helper strategy in light of recent results. The authors first place the discoveries of the HC strategy in a historical context, suggesting that HC are exclusively found in non-circulative viruses (viruses that only attach to the vector). They present an overview of the nature and modes of action of helper components in the major virus clades of non-circulative viruses (Potyviruses and Caulimoviruses). Authors then detail recent advances, to which they have significantly contributed, showing that the helper strategy also appears widespread in circulative transmission categories (Tenuiviruses, Nanoviruses). In an extensive perspective section, they raise the question of the evolutionary significance of the existence of HC in numerous unrelated viruses, transmitted by unrelated vectors through different mechanisms. They explore the hypothesis that the helper strategy evolved several times independently in distinct viral clades and for different reasons. In particular, they present several potential benefits of plant virus HC related to virus cooperation, collective transmission and effector-driven infectivity. As pointed out by both reviewers, this is a very clear and synthetic review. Di Mattia et al. present an exhaustive overview of virus HC-vector molecular interactions and address functionally and evolutionarily important questions. This review should benefit a large audience interested in host-virus interactions and transmission processes. REFERENCES (1) Ng JCK, Falk BW (2006) Virus-Vector Interactions Mediating Nonpersistent and Semipersistent Transmission of Plant Viruses. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 44, 183–212. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.phyto.44.070505.143325 (2) Di Mattia J, Zeddam J-L, Uzest M, Blanc S (2023) The helper strategy in vector-transmission of plant viruses. Zenodo, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Infections. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7709290 | The helper strategy in vector-transmission of plant viruses | Di Mattia Jérémy, Zeddam Jean Louis, Uzest Marilyne and Stéphane Blanc | <p>An intriguing aspect of vector-transmission of plant viruses is the frequent involvement of a helper component (HC). HCs are virus-encoded non-structural proteins produced in infected plant cells that are mandatory for the transmission success.... |  | Evolution of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Interactions between hosts and infectious agents/vectors, Molecular biology of infections, Molecular genetics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Plant diseases, Vectors, Viruses | Christine Coustau | 2022-10-28 17:32:39 | View | |

14 Feb 2024

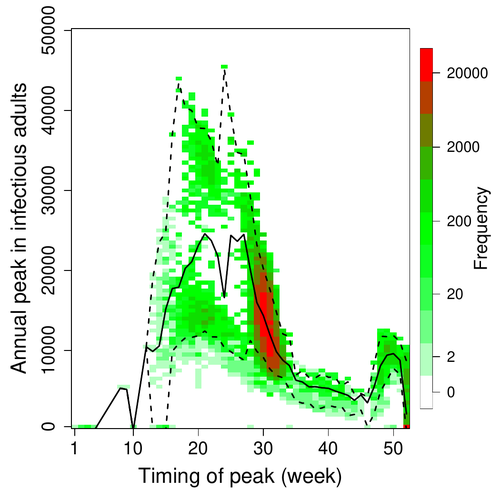

A Bayesian analysis of birth pulse effects on the probability of detecting Ebola virus in fruit batsDavid R.J. Pleydell, Innocent Ndong Bass, Flaubert Auguste Mba Djondzo, Dowbiss Meta Djomsi, Charles Kouanfack, Martine Peeters, Julien Cappelle https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.10.552777Epidemiological modeling to optimize the detection of zoonotic viruses in wild (reservoir) speciesRecommended by Aurelien Tellier based on reviews by Hetsron Legrace NYANDJO BAMEN and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Hetsron Legrace NYANDJO BAMEN and 1 anonymous reviewer

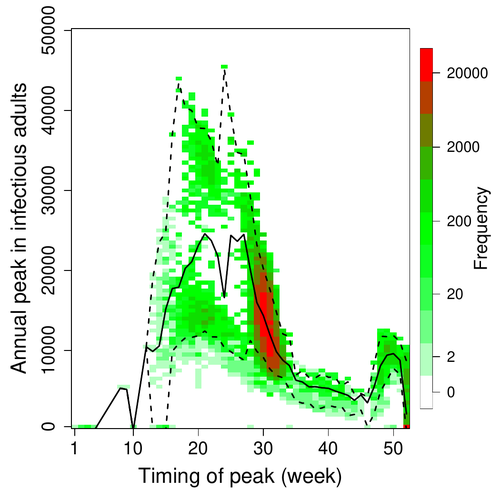

Various species of Ebolavirus have caused, and are still causing, zoonotic outbreaks and public health crises in Africa. Bats have long been hypothesized to be important reservoir populations for a series of viruses such as Hendra or Marburg viruses, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2) as well as Ebolaviruses [2, 3]. However the ecology of disease dynamics, disease transmission, and coevolution with their natural hosts of these viruses is still poorly understood, despite their importance for predicting novel outbreaks in human or livestock populations. The evidence that bats function as sylvatic reservoirs for Ebola viruses is yet only partial. Indeed, only few serological studies demonstrated the presence of Ebolavirus antibodies in young bats [4], albeit without providing positive controls of viral detection or identifying the viral species (via PCR). There is thus an unexplained discrepancy between serological data and viral detection [2, 4]. In this article, Pleydell et al. [1] use a modeling approach as well as published serological and age-structure (of the bat population) data to calibrate the model simulations. The study starts with the development of an age-structured epidemiological model which includes seasonal birth pulses and waning immunity, both generating pulses of Ebolavirus transmission within a colony of African straw-coloured fruit bats (Eidolon helvum). The epidemiological dynamics of such system of ordinary differential equations can generate annual outbreaks, skipped years or multi-annual cycles up to chaotic dynamics. Therefore, the calibration of the parameters, and the definition of biologically relevant priors, are key. To this aim, the serological data are obtained from a previous study in Cameroon [5], and the age structured of the bat population (birth and mortality) from a population study in Ghana [6]. These data are integrated into the Bayesian analysis and statistical framework to fit the model and generate predictions. In a nutshell, the authors show an overlap between the data and credibility intervals generated by the calibrated model, which thus explains well the seasonality of age-structure, namely changes in pup presence, number of lactating females, or proportion of juveniles in May. The authors can estimate that 76% of adults and 39% of young bats do survive each year, and infections are expected to last one and a half weeks. The epidemiological model predicts that annual birth pulses likely generate annual disease outbreaks, so that weeks 30 to 31 of each year, are predicted to be the best period to isolate the circulating Ebolavirus in this bat population. From the model predictions, the authors estimate the probability to have missed an infectious bat among all the samples tested by PCR being approximately of one per two thousands. The disease dynamics pattern observed in the serology data, and replicated by the model, is likely driven by seasonal pulses of young susceptible bats entering the population. This seasonal birth event increases the viral transmission, resulting in the observed peak of viral prevalence. With the inclusion of immunity waning and antibody persistence, the model results illuminate therefore why previous studies have detected only few positive cases by PCR tests, in contrast to the evidence from serological data. This study provides a first proof of principle that epidemiological modeling, despite its many simplifying assumptions, can be applied to wild species reservoirs of zoonotic diseases in order to optimize the design of field studies to detect viruses. Furthermore, such models can contribute to assess the probability and timing of zoonotic outbreaks in human or livestock populations. This article illustrates one of the manifold applications of mathematical theory of disease epidemiology to optimize sampling of pathogens/parasites or vaccine development and release [7, 8]. The further coupling of such models with population genetics theory and statistical inference methods (using parasite genome data) increasingly provide insights into the adaptation and evolution of parasites to human, crops and livestock populations [9, 10].

References [1] Pleydell D.R.J., Ndong Bass I., Mba Djondzo F.A., Djomsi D.M., Kouanfack C., Peeters M., and J. Cappelle. 2023. A Bayesian analysis of birth pulse effects on the probability of detecting Ebola virus in fruit bats. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.10.552777 [2] Caron A., Bourgarel M., Cappelle J., Liégeois F., De Nys H.M., and F. Roger. 2018. Ebola virus maintenance: if not (only) bats, what else? Viruses 10, 549. https://doi.org/10.3390/v10100549 [3] Letko M., Seifert S.N., Olival K.J., Plowright R.K., and V.J. Munster. 2020. Bat-borne virus diversity, spillover and emergence. Nature Reviews Microbiology 18, 461–471. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-0394-z [4] Leroy E.M., Kumulungui B., Pourrut X., Rouquet P., Hassanin A., Yaba P., Délicat A., Paweska J.T., Gonzalez J.P., and R. Swanepoel. 2005. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 438, 575–576. https://doi.org/10.1038/438575a [5] Djomsi D.M. et al. 2022. Dynamics of antibodies to Ebolaviruses in an Eidolon helvum bat colony in Cameroon. Viruses 14, 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14030560 [6] Peel A.J. et al. 2016. Bat trait, genetic and pathogen data from large-scale investigations of African fruit bats Eidolon helvum. Scientific data 3, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.49 [7] Nyandjo Bamen H.L., Ntaganda J.M., Tellier A. and O. Menoukeu Pamen. 2023. Impact of imperfect vaccine, vaccine trade-off and population turnover on infectious disease dynamics. Mathematics, 11(5), p.1240. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11051240 [8] Saadi N., Chi Y.L., Ghosh S., Eggo R.M., McCarthy C.V., Quaife M., Dawa J., Jit M. and A. Vassall. 2021. Models of COVID-19 vaccine prioritisation: a systematic literature search and narrative review. BMC medicine, 19, pp.1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-02190-3 [9] Maerkle, H., John S., Metzger, L., STOP-HCV Consortium, Ansari, M.A., Pedergnana, V. and Tellier, A., 2023. Inference of host-pathogen interaction matrices from genome-wide polymorphism data. bioRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.06.547816. [10] Gandon S., Day T., Metcalf C.J.E. and B.T. Grenfell. 2016. Forecasting epidemiological and evolutionary dynamics of infectious diseases. Trends in ecology & evolution, 31(10), pp.776-788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.07.010 | A Bayesian analysis of birth pulse effects on the probability of detecting Ebola virus in fruit bats | David R.J. Pleydell, Innocent Ndong Bass, Flaubert Auguste Mba Djondzo, Dowbiss Meta Djomsi, Charles Kouanfack, Martine Peeters, Julien Cappelle | <p>Since 1976 various species of Ebolavirus have caused a series of zoonotic outbreaks and public health crises in Africa. Bats have long been hypothesised to function as important hosts for ebolavirus maintenance, however the transmission ecology... |  | Animal diseases, Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecohealth, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Epidemiology, Population dynamics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Reservoirs, Viruses, Zoonoses | Aurelien Tellier | 2023-08-16 16:57:05 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Jorge Amich

Christine Chevillon

Fabrice Courtin

Christine Coustau

Thierry De Meeûs

Heather R. Jordan

Karl-Heinz Kogel

Yannick Moret

Thomas Pollet

Benjamin Roche

Benjamin Rosenthal

Bashir Salim

Lucy Weinert