WALECKX Etienne

- INTERTRYP (Host-Vector-Parasite-Environment Interactions in the Neglected Tropical Diseases due to Trypanosomatids), IRD, Mérida, Mexico

- Behaviour of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Population genetics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Vectors

- recommender

Recommendation: 1

Reviews: 0

Recommendation: 1

Zoonotic emergence at the animal-environment-human interface: the forgotten urban socio-ecosystems

Zoonotic emergence and the overlooked case of cities

Recommended by Etienne Waleckx based on reviews by Eric Dumonteil, Nicole L. Gottdenker and 1 anonymous reviewerZoonotic pathogens, those transmitted from animals to humans, constitute a major public health risk with high associated global economic costs. Diseases associated with these pathogens represent more than 60% of emerging infectious diseases and predominantly originate in wildlife (1). Over the last decades, the emergence and re-emergence of zoonotic pathogens have led to an increasing number of epidemics, as illustrated by the current Covid-19 pandemic. There is ample evidence that human impact on native ecosystems such as deforestation, agricultural development, and urbanization, is linked to spillover of pathogens from animals to humans (2). However, research and calls to action have mainly focused on the importance of surveillance and prevention of zoonotic emergences along landscape interfaces, with special emphasis on tropical forests and agroecosystems, and studies and reviews pointing out the zoonotic risk associated with cities are scarce. Additionally, cities are sometimes wrongly seen as one homogeneous ecosystem, almost exclusively human, with a Northern hemisphere-biased perception of what a city is, which fails to take into account the ecological and socio-economic diversities that can constitute an urban area.

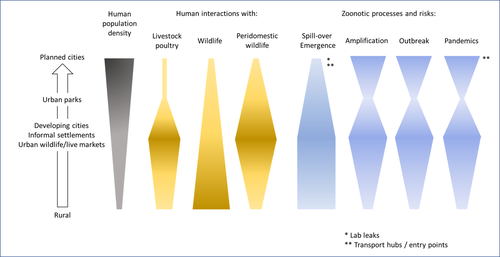

Here, Dobigny and Morand (3) aim to draw attention to the importance of urban ecosystems in zoonotic risk and advocate that further attention should be paid to urban, peri-urban and suburban areas. In this well-organized and well-documented review, the authors show, using updated literature, that cities are places where massive contacts occur between wildlife, domestic animals, and human inhabitants (thus constituting spillover opportunities), and that it is even likely that human and wildlife contact in urban centers is more prevalent than in wild areas, perhaps contrary to intuition. Indeed, cities currently constitute the most important environment of human life and are places for millions of close interactions between humans and animals, including pets and domestic animals, wild animals through the intrusion of wild urban-adapted species (e.g., some bat, rodent, or bird species among others), manipulation and consumption of wildlife meat, and the existence of wildlife meat markets, which all constitute a major risk for zoonotic spillover. In cities, lab escapees of zoonotic pathogens also exist, and trends of adaptation to urban ecological conditions of many vectors of primary health importance is also a concern. The authors further argue that cities are predominant places for both epidemic amplification of human-human transmitted pathogens, because they are places with high human densities and population growth, and for dissemination of reservoirs, vectors and pathogens, as they are transport hubs. Dobigny & Morand further predict, likely correctly, that cities may be important places for pathogen evolution. Finally, they propose actions and recommendations to limit the risk of zoonotic spillover events from urban ecosystems and future directions for research aiming at assessing this risk.

The reviewers found the manuscript well-organized and presented, timely, and bringing novel contributions to the field of zoonotic emergence. I strongly recommend this article, which should benefit a large audience, particularly in the context of the current Covid-19 pandemics and the ongoing One Health initiatives aiming at preventing future zoonotic disease emergence (4).

References

(1) Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, Daszak P (2008) Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature, 451, 990–993. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06536

(2) White RJ, Razgour O (2020) Emerging zoonotic diseases originating in mammals: a systematic review of effects of anthropogenic land-use change. Mammal Review, 50, 336–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/mam.12201

(3) Dobigny G, Morand S (2022) Zoonotic emergence at the animal-environment-human interface: the forgotten urban socio-ecosystems. Zenodo, 6444776, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6444776

(4) Morand S, Lajaunie C (2021) Biodiversity and COVID-19: A report and a long road ahead to avoid another pandemic. One Earth, 4, 920–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.06.007