GUÉGAN Jean-Francois

- Department of Animal Health/Department of Societies & Health, INRAE-IRD, Montpellier, France

- Animal diseases, Coevolution, Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Epidemiology, Geography of infectious diseases, Interactions between hosts and infectious agents/vectors, Microbiology of infections, Parasites, Population dynamics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Reservoirs, Sapronoses, Zoonoses

- recommender

Recommendations: 3

Reviews: 0

Recommendations: 3

Spatial and temporal epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 virus lineages in Teesside, UK, in 2020: effects of socio-economic deprivation, weather, and lockdown on lineage dynamics

Small-scale study reveals the role of socio-economic deprivation, weather and local versus national health decisions on SARS-3 CoV-2 virus lineage dynamics

Recommended by Jean-Francois Guégan based on reviews by Samuel Alizon and 2 anonymous reviewersEach and every one of us will recall the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus (CoV-2) pandemic, and the national and international political hesitations in its management. Fall 2019, in the city of Wuhan, Hubei province, China, an outbreak of unusual viral pneumonia due to a new emerging coronavirus named as SARS-CoV-2 started, generating late February a modern pandemic called COVID-19, posing very serious threat to global public health and the world economy (Hu et al. 2021). As we are getting out from this pandemic, and even if viral variants are still circulating, what have we learned and retained from this difficult period, shaking our certainties and reminding us of past images of devastating plagues? The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of early action, widespread testing, open data sharing, and strong public responses (The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2024). It has also highlighted that the animal origin of SARS-CoV-2 was still unknown and the existence of a reservoir host not really demonstrated (Cohen 2021). Beyond this, the COVID-19 pandemic has also revealed the importance of early and continuous surveillance, also raised questions about the role of meteorological conditions on the dispersion and viability of this virus, and highlighted the devastating effects of social inequality. We all remember some medical doctors who became modern preachers announcing the end of the pandemic because of unfavorable weather conditions coming for viral spread!

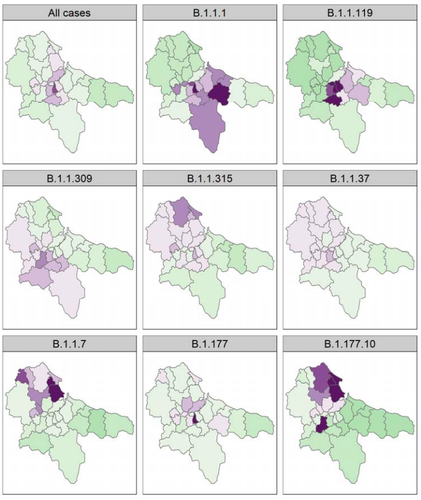

However, epidemiological studies analyzing the role of different parameters, and effects of national and regional restrictions at local or regional scales on COVID-19 are still rare. In this investigation entitled “Spatial and temporal epidemiology of SARS-3 CoV-2 virus lineages in Teesside, UK, in 2020: effects of socio-economic deprivation, weather, and lockdown on lineage dynamics”, Moss and collaborators’ aim is to analyze how a range of parameters, using both generalized linear mixed- and Bayesian spatial modeling, affected positive cases in the Teesside subregion of North East England during 2020 (Moss et al. 2024). Also, the authors wanted to understand the impacts of national and local government interventions introduced this year affected disease conditions in this subregion showing high levels of deprivation due to deindustrialisation in the latter half of the 20th century.

According to Moss et al. (2024), the UK government decided for a heterogenous ”tier” system of local restrictions in England during the second wave associated with a more stringent national lockdown. The intention was to be more responsive and appropriate to the different English local contexts. The authors take us through a detailed statistical analysis to show that disease patterns in Teesside were associated with demographic parameters, social deprivation, weather conditions (essentially temperature) and governmental health interventions. Interestingly, findings lead to the conclusion that local tier interventions by public authorities was less effective at reducing COVID-19 cases in Teesside than a strict, long-term national lockdown. A closer look at the spatio-temporal dynamics of the eight most common SARS-CoV-2 lineages circulating in Teesside in 2020 reveals complex dynamic behaviours differing to those of the total positive cases, certainly due to environmental and demographic stochasticity, and sublocal heterogenous social and economic conditions.

Overall, we recommend reading this study, which reveals the complexity of dealing with epidemics and pandemics, and highlights the importance of sound national political decisions and difficulties to proceed to local adjustments, i.e. tier system, in epidemic and pandemic control.

The present recommendation is resulting from thorough reviews produced by Samuel Alizon and two anonymous reviewers, and which I thank very much for their review works here.

References

Jon COHEN. 2021. Prophet in purgatory. Science 374, 1040-1045. https://www.science.org/doi/epdf/10.1126/science.acx9661

Ben HU, Hua GUO, Peng ZHOU, Zheng-Li SHI. 2021. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol 19, 141-54. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7

The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2024. Have we learned anything? Editorial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 24, 793. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00439-0

E.D. Moss, S.P. Rushton, P. Baker, M. Bashton, M.R. Crown, R.N. dos Santos, A. Nelson, S.J. O’Brien, Z. Richards, R.A. Sanderson, W.C. Yew, G.R. Young, C.M. McCann, D.L. Smith (2024) Spatial and temporal epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 virus lineages in Teesside, UK, in 2020: effects of socio-economic deprivation, weather, and lockdown on lineage dynamics. medRxiv, ver.5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.05.22269279

Diverse fox circovirus (Circovirus canine) variants circulate at high prevalence in grey wolves (Canis lupus) from the Northwest Territories, Canada

Wild canine viruses in the news. Better understanding multi-host transmission by adopting a disease ecology species community-based approach

Recommended by Jean-Francois Guégan based on reviews by Arvind Varsani and 1 anonymous reviewerAccording to the international animal health authority, i.e., the World Organization on Animal Health (WOAH, former OIE), circoviruses are part of the Circoviridae family, which only includes 2 genera Circovirus and Cyclovirus, and infect swine, canine, ursid, viverrid, felid, pinniped, herpestid, mustelid, and several avian species (WOAH 2021). They are small (12–27 nm), non-enveloped, circular, single-stranded DNA viruses, viral replication is nuclear, and wild and domestic birds and mammals could serve as natural hosts. If most infections caused by circoviruses are subclinical in both wild and domestic species, they can be responsible for severe diseases in the commercial pig industry due to the Porcine circovirus-2 (PCV-2). These viruses can constitute a threat to wildlife, and cause their hosts to become immunocompromised, and animals often present with secondary coinfections.

Canine circoviruses (CanineCV) harbour a worldwide distribution in dogs, and is the sole member of the viral genus to infect canines. They can be detected in wild carnivores, such as wolves, badgers, foxes and jackals, which indicates an ability for cross-species transmission between wildlife and domestic dogs. However, fox circovirus (FoCV), a distinct lineage of CanineCV, has been identified exclusively in wild canids (foxes and wolves) and not in dogs in Europe and North America, where it can cause in red foxes meningoencephalitis and other central nervous system signs.

In their article, Canuti et al. (2024) investigate the presence, distribution and ecology of CanineCV in grey wolf specimens from the Northwest Territories, Canada. CanineCV occurrence appears to be relatively high with 45.3% positive specimens and parvoviral superinfections observed. The authors identify a high CanineCV genetic diversity among the investigated grey wolf specimens, and exacerbated by viral recombination. Phylogenetic analysis reveals the existence of 4 lineages, within each of them strains segregate by geography and not by host origin. This observed geographic segregation is interpreted as being due to the absence of exchange flows between grey wolf host subpopulations. Due to the paucity of knowledge on these circoviruses in wildlife and at the interface between wild and domestic animals, the authors discuss the plausible role of wolves as natural host reservoirs for disease transmission due to long-lasting virus-host coevolution. They are also conscious that additional maintenance hosts could exist in the wild, claiming for further studies to decipher fox circovirus disease ecology and transmission dynamics.

This study underlines the importance of better understanding the transmission ecology and evolution of these Canine circoviruses, and I can only agree. Xiao et al. (2023), a research not referred to in the present work, evidenced CanineCV infection in cats in China, and obtained the first whole genome of cat-derived CanineCV. This emphasizes the importance of monitoring additional animal species and locations in the world to clarify disease ecology and transmission dynamics. A broader sampling of a wide range of animal species in different parts of the world using a species community-based approach is the key to understanding these CanineCV infections.

References

Marta CANUTI, Abigail V.L. KING, Giovanni FRANZO, H. Dean CLUFF, Lars E. LARSEN, Heather FENTON, Suzanne C. DUFOUR, Andrew S. LANG. 2024. Diverse fox circovirus (Circovirus canine) variants circulate at high prevalence in grey wolves (Canis lupus) from the Northwest Territories, Canada. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.08.584028

World Organization on Animal Health. 2021. Circoviruses. https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2021/05/circoviruses-infection-with.pdf [consulted on July 9th, 2024].

Xiangyu XIAO, Yan CHAO LI, Feng PEI XU, Xiangpi HAO, Shoujun LI, Pei ZHOU. 2023. Canine circovirus among dogs and cats in China: first identification in cats. Front. Microbiol. 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1252272

Assessing the dynamics of Mycobacterium bovis infection in three French badger populations

From disease surveillance to public action. Re-inforcing both epidemiological surveillance and data analysis: an illustration with Mycobacterium bovis

Recommended by Jean-Francois Guégan based on reviews by Rowland Kao and 1 anonymous reviewerMycobacterium bovis, also called M. tuberculosis var. bovis, is a bacterium belonging to the M. tuberculosis complex (i.e., MTBC) and which can cause through zoonotic transmission another form of human tuberculosis (Tb). It is above all the agent of bovine tuberculosis (i.e., bTb) which affects not only cattle (wild or farmed) but also a large diversity of other wild mammals worldwide. An increasing number of infected animal cases are being discovered in many regions of the world, thus raising the problem of tuberculosis transmission, including to humans, more complex than previously thought. Efforts have been made in terms of vaccination or culling of populations of host carrier species, such as the badger for example, however leading to consequences of greater dispersion of the infectious agent. M. bovis shows a more or less significant capacity to persist outside its hosts, particularly in the environment under certain abiotic and biotic conditions. This bacillus can be transmitted and spread in many ways, including through aerosol, mucus and sputum, urine and feces, by direct contact with infected animals, their dead bodies or rather via their excreta or by inhalation of aerosols, depending on the host species concerned.

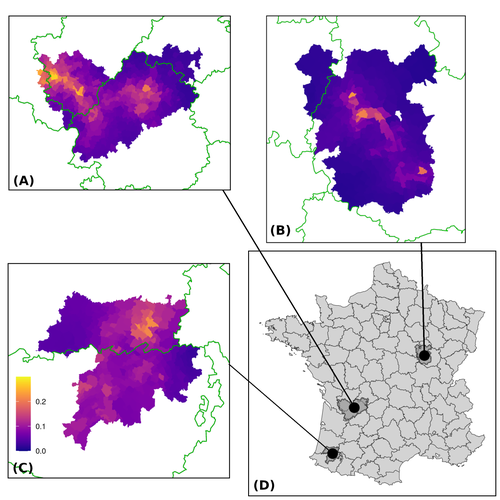

In this paper, Calenge and his collaborators (Callenge et al. 2024) benefited from a national surveillance program on M. bovis cases in wild species, set up in 2011 in France, i.e., Sylvatub, for detecting and monitoring M. bovis infection in European badger (Meles meles) populations. Sylvatub is a participatory program involving both national and local stakeholder systems in order to determine changes in bTb infection levels in domestic and wild animal species. This original work had two aims: to describe spatial disease dynamics in the three clusters under scrutiny using a complex Bayesian model; and to develop indicators for the monitoring of the M. bovis infection by stakeholders and decision-makers of the program. This paper is timely and very comprehensive.

In this cogent study, the authors illustrate this point by using epidemiological surveillance to obtain large amounts of data (which is generally lacking in human epidemiology, but more dramatically lacking in animal epidemiology) and a highly sophisticated biostatistical analysis (Callenge et al. 2024). It is in itself a demonstration of the current capabilities of population dynamics applied to infectious disease situations, in this case animal, in the rapidly developing discipline of disease ecology and evolution. One of the aims of the study is to propose statistical models that can be used by the different stakeholders in charge, for instance, of wildlife conservation or the regional or State veterinary services to assess disease risk in the most affected regions.

References

Assel AKHMETOVA, Jimena GUERRERO, Paul McADAM, Liliana CM SALVADOR, Joseph CRISPELL, John LAVERY, Eleanor PRESHO, Rowland R KAO, Roman BIEK, Fraser MENZIES, Nigel TRIMBLE, Roland HARWOOD, P Theo PEPLER, Katarina ORAVCOVA, Jordon GRAHAM, Robin SKUCE, Louis DU PLESSIS, Suzan THOMPSON, Lorraine WRIGHT, Andrew W BYRNE, Adrian R ALLEN. 2023. Genomic epidemiology of Mycobacterium bovis infection in sympatric badger and cattle populations in Northern Ireland. Microbial Genomics 9: mgen001023. https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.001023

Roman BIEK, Anthony O’HARE, David WRIGHT, Tom MALLON, Carl McCORMICK, Richard J ORTON, Stanley McDOWELL, Hannah TREWBY, Robin A SKUCE, Rowland R KAO. 2012. Whole genome sequencing reveals local transmission patterns of Mycobacterium bovis in sympatric cattle and badger populations. PLoS Pathogens 8: e1003008. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003008

Clément CALENGE, Ariane PAYNE, Edouard REVEILLAUD, Céline RICHOMME, Sébastien GIRARD, Stephanie DESVAUX. 2024. Assessing the dynamics of Mycobacterium bovis infection in three French badger populations. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.31.543041

Marc CHOISY, Pejman ROHANI. 2006. Harvesting can increase severity of wildlife disease epidemics. Proceedings of the Royal Society, London, Ser. B 273: 2025-2034. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3554

Shannon C DUFFY, Sreenidhi SRINIVASAN, Megan A SCHILLING, Tod STUBER, Sarah N DANCHUK, Joy S MICHAEL, Manigandan VENKATESAN, Nitish BANSAL, Sushila MAAN, Naresh JINDAL, Deepika CHAUDHARY, Premanshu DANDAPAT, Robab KATANI, Shubhada CHOTHE, Maroudam VEERASAMI, Suelee ROBBE-AUSTERMAN, Nicholas JULEFF, Vivek KAPUR, Marcel A BEHR. 2020. Reconsidering Mycobacterium bovis as a proxy for zoonotic tuberculosis: a molecular epidemiological surveillance study. Lancet Microbe 1: e66-e73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30038-0

Jean-François GUEGAN. 2019. The nature of ecology of infectious disease. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 19. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(19)30529-8

Brandon H HAYES, Timothée VERGNE, Mathieu ANDRAUD, Nicolas ROSE. 2023. Mathematical modeling at the livestock-wildlife interface: scoping review of drivers of disease transmission between species. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 10: 1225446. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1225446

David KING, Tim ROPER, Douglas YOUNG, Mark EJ WOOLHOUSE, Dan COLLINS, Paul WOOD. 2007. Bovine tuberculosis in cattle and badgers. Report to Secretary of State about tuberculosis in cattle and badgers. London, UK.

Robert MM SMITH , Francis DROBNIEWSKI, Andrea GIBSON, John DE MONTAGUE, Margaret N LOGAN, David HUNT, Glyn HEWINSON, Roland L SALMON, Brian O’NEILL. 2004. Mycobacterium bovis Infection, United Kingdom. Emerging Infectious Diseases 10: 539-541. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1003.020819