Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields▼ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

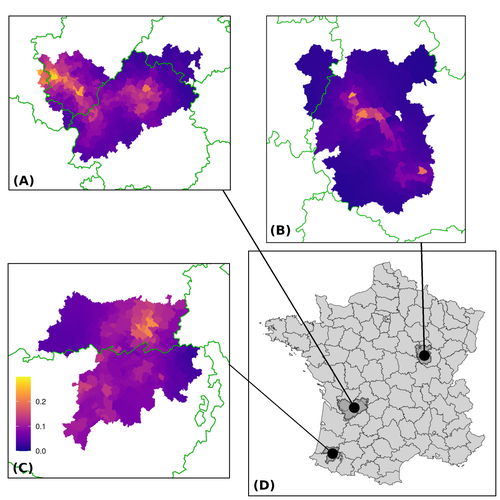

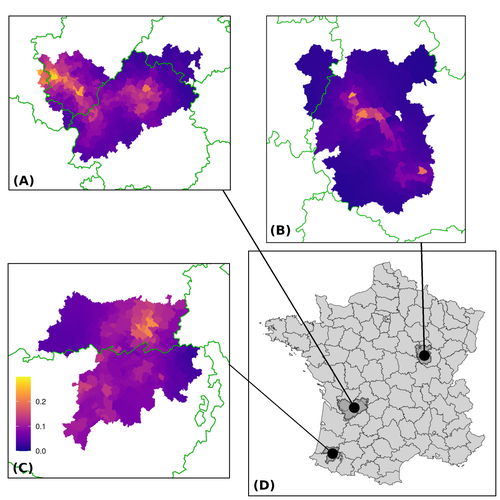

17 Jan 2024

Assessing the dynamics of Mycobacterium bovis infection in three French badger populationsClement CALENGE, Ariane PAYNE, Edouard REVEILLAUD, Celine RICHOMME, Sebastien GIRARD, Stephanie DESVAUX https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.31.543041From disease surveillance to public action. Re-inforcing both epidemiological surveillance and data analysis: an illustration with Mycobacterium bovisRecommended by Jean-Francois Guegan based on reviews by Rowland Kao and 1 anonymous reviewerMycobacterium bovis, also called M. tuberculosis var. bovis, is a bacterium belonging to the M. tuberculosis complex (i.e., MTBC) and which can cause through zoonotic transmission another form of human tuberculosis (Tb). It is above all the agent of bovine tuberculosis (i.e., bTb) which affects not only cattle (wild or farmed) but also a large diversity of other wild mammals worldwide. An increasing number of infected animal cases are being discovered in many regions of the world, thus raising the problem of tuberculosis transmission, including to humans, more complex than previously thought. Efforts have been made in terms of vaccination or culling of populations of host carrier species, such as the badger for example, however leading to consequences of greater dispersion of the infectious agent. M. bovis shows a more or less significant capacity to persist outside its hosts, particularly in the environment under certain abiotic and biotic conditions. This bacillus can be transmitted and spread in many ways, including through aerosol, mucus and sputum, urine and feces, by direct contact with infected animals, their dead bodies or rather via their excreta or by inhalation of aerosols, depending on the host species concerned. In this paper, Calenge and his collaborators (Callenge et al. 2024) benefited from a national surveillance program on M. bovis cases in wild species, set up in 2011 in France, i.e., Sylvatub, for detecting and monitoring M. bovis infection in European badger (Meles meles) populations. Sylvatub is a participatory program involving both national and local stakeholder systems in order to determine changes in bTb infection levels in domestic and wild animal species. This original work had two aims: to describe spatial disease dynamics in the three clusters under scrutiny using a complex Bayesian model; and to develop indicators for the monitoring of the M. bovis infection by stakeholders and decision-makers of the program. This paper is timely and very comprehensive. In this cogent study, the authors illustrate this point by using epidemiological surveillance to obtain large amounts of data (which is generally lacking in human epidemiology, but more dramatically lacking in animal epidemiology) and a highly sophisticated biostatistical analysis (Callenge et al. 2024). It is in itself a demonstration of the current capabilities of population dynamics applied to infectious disease situations, in this case animal, in the rapidly developing discipline of disease ecology and evolution. One of the aims of the study is to propose statistical models that can be used by the different stakeholders in charge, for instance, of wildlife conservation or the regional or State veterinary services to assess disease risk in the most affected regions. References Assel AKHMETOVA, Jimena GUERRERO, Paul McADAM, Liliana CM SALVADOR, Joseph CRISPELL, John LAVERY, Eleanor PRESHO, Rowland R KAO, Roman BIEK, Fraser MENZIES, Nigel TRIMBLE, Roland HARWOOD, P Theo PEPLER, Katarina ORAVCOVA, Jordon GRAHAM, Robin SKUCE, Louis DU PLESSIS, Suzan THOMPSON, Lorraine WRIGHT, Andrew W BYRNE, Adrian R ALLEN. 2023. Genomic epidemiology of Mycobacterium bovis infection in sympatric badger and cattle populations in Northern Ireland. Microbial Genomics 9: mgen001023. https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.001023 Roman BIEK, Anthony O’HARE, David WRIGHT, Tom MALLON, Carl McCORMICK, Richard J ORTON, Stanley McDOWELL, Hannah TREWBY, Robin A SKUCE, Rowland R KAO. 2012. Whole genome sequencing reveals local transmission patterns of Mycobacterium bovis in sympatric cattle and badger populations. PLoS Pathogens 8: e1003008. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003008 Clément CALENGE, Ariane PAYNE, Edouard REVEILLAUD, Céline RICHOMME, Sébastien GIRARD, Stephanie DESVAUX. 2024. Assessing the dynamics of Mycobacterium bovis infection in three French badger populations. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.31.543041 Marc CHOISY, Pejman ROHANI. 2006. Harvesting can increase severity of wildlife disease epidemics. Proceedings of the Royal Society, London, Ser. B 273: 2025-2034. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3554 Shannon C DUFFY, Sreenidhi SRINIVASAN, Megan A SCHILLING, Tod STUBER, Sarah N DANCHUK, Joy S MICHAEL, Manigandan VENKATESAN, Nitish BANSAL, Sushila MAAN, Naresh JINDAL, Deepika CHAUDHARY, Premanshu DANDAPAT, Robab KATANI, Shubhada CHOTHE, Maroudam VEERASAMI, Suelee ROBBE-AUSTERMAN, Nicholas JULEFF, Vivek KAPUR, Marcel A BEHR. 2020. Reconsidering Mycobacterium bovis as a proxy for zoonotic tuberculosis: a molecular epidemiological surveillance study. Lancet Microbe 1: e66-e73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30038-0 Jean-François GUEGAN. 2019. The nature of ecology of infectious disease. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 19. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(19)30529-8 Brandon H HAYES, Timothée VERGNE, Mathieu ANDRAUD, Nicolas ROSE. 2023. Mathematical modeling at the livestock-wildlife interface: scoping review of drivers of disease transmission between species. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 10: 1225446. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1225446 David KING, Tim ROPER, Douglas YOUNG, Mark EJ WOOLHOUSE, Dan COLLINS, Paul WOOD. 2007. Bovine tuberculosis in cattle and badgers. Report to Secretary of State about tuberculosis in cattle and badgers. London, UK. https://www.bovinetb.info/docs/RBCT_david_%20king_report.pdf Robert MM SMITH , Francis DROBNIEWSKI, Andrea GIBSON, John DE MONTAGUE, Margaret N LOGAN, David HUNT, Glyn HEWINSON, Roland L SALMON, Brian O’NEILL. 2004. Mycobacterium bovis Infection, United Kingdom. Emerging Infectious Diseases 10: 539-541. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1003.020819 | Assessing the dynamics of *Mycobacterium bovis* infection in three French badger populations | Clement CALENGE, Ariane PAYNE, Edouard REVEILLAUD, Celine RICHOMME, Sebastien GIRARD, Stephanie DESVAUX | <p>The Sylvatub system is a national surveillance program established in 2011 in France to monitor infections caused by <em>Mycobacterium bovis</em>, the main etiologic agent of bovine tuberculosis, in wild species. This participatory program, inv... |  | Animal diseases, Ecohealth, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Epidemiology, Geography of infectious diseases, Pathogenic/Symbiotic Bacteria, Zoonoses | Jean-Francois Guegan | 2023-06-05 10:50:49 | View | |

28 Oct 2022

Development of nine microsatellite loci for Trypanosoma lewisi, a potential human pathogen in Western Africa and South-East Asia, and preliminary population genetics analysesAdeline Ségard, Audrey Romero, Sophie Ravel, Philippe Truc, Gauthier Dobigny, Philippe Gauthier, Jonas Etougbetche, Henri-Joel Dossou, Sylvestre Badou, Gualbert Houéménou, Serge Morand, Kittipong Chaisiri, Camille Noûs, Thierry deMeeûs https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6460010Preliminary population genetic analysis of Trypanosoma lewisiRecommended by Annette MacLeod based on reviews by Gabriele Schönian and 1 anonymous reviewerTrypanosoma lewisi is an atypical trypanosome species. Transmitted by fleas, it has a high prevalence and worldwide distribution in small mammals, especially rats [1]. Although not typically thought to infect humans, there has been a number of reports of human infections by T. lewisi in Asia including a case of a fatal infection in an infant [2]. The fact that the parasite is resistant to lysis by normal human serum [3] suggests that many people, especially immunocompromised individuals, may be at risk from zoonotic infections by this pathogen, particularly in regions where there is close contact with T. lewisi-infected rat fleas. Indeed, it is also possible that cryptic T. lewisi infections exist but have hitherto gone undetected. Such asymptomatic infections have been detected for a number of parasitic infections including the related parasite T. b. gambiense [4]. References

[2] Truc P, Büscher P, Cuny G, Gonzatti MI, Jannin J, Joshi P, Juyal P, Lun Z-R, Mattioli R, Pays E, Simarro PP, Teixeira MMG, Touratier L, Vincendeau P, Desquesnes M (2013) Atypical Human Infections by Animal Trypanosomes. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 7, e2256. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002256 [3] Lun Z-R, Wen Y-Z, Uzureau P, Lecordier L, Lai D-H, Lan Y-G, Desquesnes M, Geng G-Q, Yang T-B, Zhou W-L, Jannin JG, Simarro PP, Truc P, Vincendeau P, Pays E (2015) Resistance to normal human serum reveals Trypanosoma lewisi as an underestimated human pathogen. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology, 199, 58–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molbiopara.2015.03.007 [4] Büscher P, Bart J-M, Boelaert M, Bucheton B, Cecchi G, Chitnis N, Courtin D, Figueiredo LM, Franco J-R, Grébaut P, Hasker E, Ilboudo H, Jamonneau V, Koffi M, Lejon V, MacLeod A, Masumu J, Matovu E, Mattioli R, Noyes H, Picado A, Rock KS, Rotureau B, Simo G, Thévenon S, Trindade S, Truc P, Reet NV (2018) Do Cryptic Reservoirs Threaten Gambiense-Sleeping Sickness Elimination? Trends in Parasitology, 34, 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2017.11.008 [5] Ségard A, Roméro A, Ravel S, Truc P, Gauthier D, Gauthier P, Dossou H-J, Sylvestre B, Houéménou G, Morand S, Chaisiri K, Noûs C, De Meeûs T (2022) Development of nine microsatellite loci for Trypanosoma lewisi, a potential human pathogen in Western Africa and South-East Asia, and preliminary population genetics analyses. Zenodo, 6460010, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6460010 | Development of nine microsatellite loci for Trypanosoma lewisi, a potential human pathogen in Western Africa and South-East Asia, and preliminary population genetics analyses | Adeline Ségard, Audrey Romero, Sophie Ravel, Philippe Truc, Gauthier Dobigny, Philippe Gauthier, Jonas Etougbetche, Henri-Joel Dossou, Sylvestre Badou, Gualbert Houéménou, Serge Morand, Kittipong Chaisiri, Camille Noûs, Thierry deMeeûs | <p><em>Trypanosoma lewisi</em> belongs to the so-called atypical trypanosomes that occasionally affect humans. It shares the same hosts and flea vector of other medically relevant pathogenic agents as Yersinia pestis, the agent of plague. Increasi... |  | Animal diseases, Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Eukaryotic pathogens/symbionts, Evolution of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Microbiology of infections, Parasites, Population genetics of hosts, in... | Annette MacLeod | 2022-04-21 17:04:37 | View | |

14 Feb 2024

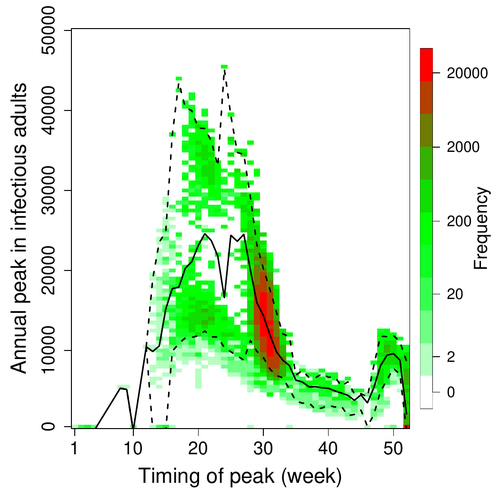

A Bayesian analysis of birth pulse effects on the probability of detecting Ebola virus in fruit batsDavid R.J. Pleydell, Innocent Ndong Bass, Flaubert Auguste Mba Djondzo, Dowbiss Meta Djomsi, Charles Kouanfack, Martine Peeters, Julien Cappelle https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.10.552777Epidemiological modeling to optimize the detection of zoonotic viruses in wild (reservoir) speciesRecommended by Aurelien Tellier based on reviews by Hetsron Legrace NYANDJO BAMEN and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Hetsron Legrace NYANDJO BAMEN and 1 anonymous reviewer

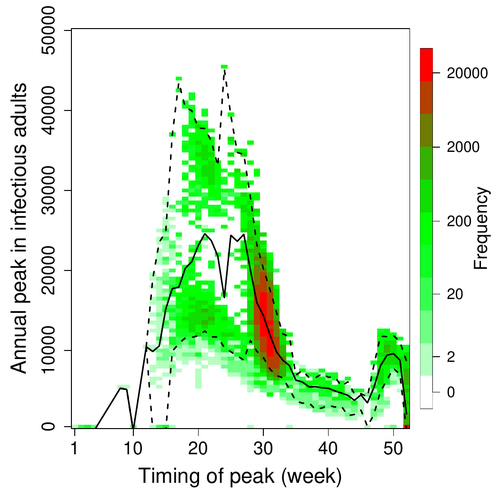

Various species of Ebolavirus have caused, and are still causing, zoonotic outbreaks and public health crises in Africa. Bats have long been hypothesized to be important reservoir populations for a series of viruses such as Hendra or Marburg viruses, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2) as well as Ebolaviruses [2, 3]. However the ecology of disease dynamics, disease transmission, and coevolution with their natural hosts of these viruses is still poorly understood, despite their importance for predicting novel outbreaks in human or livestock populations. The evidence that bats function as sylvatic reservoirs for Ebola viruses is yet only partial. Indeed, only few serological studies demonstrated the presence of Ebolavirus antibodies in young bats [4], albeit without providing positive controls of viral detection or identifying the viral species (via PCR). There is thus an unexplained discrepancy between serological data and viral detection [2, 4]. In this article, Pleydell et al. [1] use a modeling approach as well as published serological and age-structure (of the bat population) data to calibrate the model simulations. The study starts with the development of an age-structured epidemiological model which includes seasonal birth pulses and waning immunity, both generating pulses of Ebolavirus transmission within a colony of African straw-coloured fruit bats (Eidolon helvum). The epidemiological dynamics of such system of ordinary differential equations can generate annual outbreaks, skipped years or multi-annual cycles up to chaotic dynamics. Therefore, the calibration of the parameters, and the definition of biologically relevant priors, are key. To this aim, the serological data are obtained from a previous study in Cameroon [5], and the age structured of the bat population (birth and mortality) from a population study in Ghana [6]. These data are integrated into the Bayesian analysis and statistical framework to fit the model and generate predictions. In a nutshell, the authors show an overlap between the data and credibility intervals generated by the calibrated model, which thus explains well the seasonality of age-structure, namely changes in pup presence, number of lactating females, or proportion of juveniles in May. The authors can estimate that 76% of adults and 39% of young bats do survive each year, and infections are expected to last one and a half weeks. The epidemiological model predicts that annual birth pulses likely generate annual disease outbreaks, so that weeks 30 to 31 of each year, are predicted to be the best period to isolate the circulating Ebolavirus in this bat population. From the model predictions, the authors estimate the probability to have missed an infectious bat among all the samples tested by PCR being approximately of one per two thousands. The disease dynamics pattern observed in the serology data, and replicated by the model, is likely driven by seasonal pulses of young susceptible bats entering the population. This seasonal birth event increases the viral transmission, resulting in the observed peak of viral prevalence. With the inclusion of immunity waning and antibody persistence, the model results illuminate therefore why previous studies have detected only few positive cases by PCR tests, in contrast to the evidence from serological data. This study provides a first proof of principle that epidemiological modeling, despite its many simplifying assumptions, can be applied to wild species reservoirs of zoonotic diseases in order to optimize the design of field studies to detect viruses. Furthermore, such models can contribute to assess the probability and timing of zoonotic outbreaks in human or livestock populations. This article illustrates one of the manifold applications of mathematical theory of disease epidemiology to optimize sampling of pathogens/parasites or vaccine development and release [7, 8]. The further coupling of such models with population genetics theory and statistical inference methods (using parasite genome data) increasingly provide insights into the adaptation and evolution of parasites to human, crops and livestock populations [9, 10].

References [1] Pleydell D.R.J., Ndong Bass I., Mba Djondzo F.A., Djomsi D.M., Kouanfack C., Peeters M., and J. Cappelle. 2023. A Bayesian analysis of birth pulse effects on the probability of detecting Ebola virus in fruit bats. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.10.552777 [2] Caron A., Bourgarel M., Cappelle J., Liégeois F., De Nys H.M., and F. Roger. 2018. Ebola virus maintenance: if not (only) bats, what else? Viruses 10, 549. https://doi.org/10.3390/v10100549 [3] Letko M., Seifert S.N., Olival K.J., Plowright R.K., and V.J. Munster. 2020. Bat-borne virus diversity, spillover and emergence. Nature Reviews Microbiology 18, 461–471. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-0394-z [4] Leroy E.M., Kumulungui B., Pourrut X., Rouquet P., Hassanin A., Yaba P., Délicat A., Paweska J.T., Gonzalez J.P., and R. Swanepoel. 2005. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 438, 575–576. https://doi.org/10.1038/438575a [5] Djomsi D.M. et al. 2022. Dynamics of antibodies to Ebolaviruses in an Eidolon helvum bat colony in Cameroon. Viruses 14, 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14030560 [6] Peel A.J. et al. 2016. Bat trait, genetic and pathogen data from large-scale investigations of African fruit bats Eidolon helvum. Scientific data 3, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.49 [7] Nyandjo Bamen H.L., Ntaganda J.M., Tellier A. and O. Menoukeu Pamen. 2023. Impact of imperfect vaccine, vaccine trade-off and population turnover on infectious disease dynamics. Mathematics, 11(5), p.1240. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11051240 [8] Saadi N., Chi Y.L., Ghosh S., Eggo R.M., McCarthy C.V., Quaife M., Dawa J., Jit M. and A. Vassall. 2021. Models of COVID-19 vaccine prioritisation: a systematic literature search and narrative review. BMC medicine, 19, pp.1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-02190-3 [9] Maerkle, H., John S., Metzger, L., STOP-HCV Consortium, Ansari, M.A., Pedergnana, V. and Tellier, A., 2023. Inference of host-pathogen interaction matrices from genome-wide polymorphism data. bioRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.06.547816. [10] Gandon S., Day T., Metcalf C.J.E. and B.T. Grenfell. 2016. Forecasting epidemiological and evolutionary dynamics of infectious diseases. Trends in ecology & evolution, 31(10), pp.776-788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.07.010 | A Bayesian analysis of birth pulse effects on the probability of detecting Ebola virus in fruit bats | David R.J. Pleydell, Innocent Ndong Bass, Flaubert Auguste Mba Djondzo, Dowbiss Meta Djomsi, Charles Kouanfack, Martine Peeters, Julien Cappelle | <p>Since 1976 various species of Ebolavirus have caused a series of zoonotic outbreaks and public health crises in Africa. Bats have long been hypothesised to function as important hosts for ebolavirus maintenance, however the transmission ecology... |  | Animal diseases, Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecohealth, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Epidemiology, Population dynamics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Reservoirs, Viruses, Zoonoses | Aurelien Tellier | 2023-08-16 16:57:05 | View | |

25 Apr 2023

The distribution, phenology, host range and pathogen prevalence of Ixodes ricinus in France: a systematic map and narrative reviewGrégoire Perez, Laure Bournez, Nathalie Boulanger, Johanna Fite, Barbara Livoreil, Karen D. McCoy, Elsa Quillery, Magalie René-Martellet, and Sarah I. Bonnet https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.18.537315An extensive review of Ixodes ricinus in European FranceRecommended by Ana Sofia Santos based on reviews by Ana Palomar and 1 anonymous reviewerTicks are obligate, bloodsucking, nonpermanent ectoparasitic arthropods. Among them, Ixodes ricinus is a classic example of an extreme generalist tick, presenting a highly permissive feeding behavior using different groups of vertebrates as hosts, such as mammalian (including humans), avian and reptilian species (Hoogstraal & Aeschlimann, 1982; Dantas-Torresa & Otranto, 2013). This ecological adaptation can account for the broad geographical distribution of I. ricinus populations, which extends from the western end of the European continent to the Ural Mountains in Russia, and from northern Norway to the Mediterranean basin, including the North African countries - Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia (https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/disease-vectors/surveillance-and-disease-data/tick-maps). The contact with different hosts also promotes the exposure/acquisition and transmission of various pathogenic agents (viruses, bacteriae, protists and nematodes) of veterinary and medical relevance (Aeschlimann et al., 1979). As one of the prime ticks found on humans, this species is implicated in diseases such as Lyme borreliosis, Spotted Fever Group rickettsiosis, Human Anaplasmosis, Human Babesiosis and Tick-borne Encephalitis (Velez et al., 2023). The climate change projections drawn for I. ricinus, in the scenario of global warming, point for the expansion/increase activity in both latitude and altitude (Medlock et al., 2013). The adequacy of vector modeling is relaying in the proper characterization of complex biological systems. Thus, it is essential to increase knowledge on I. ricinus, focusing on aspects such as genetic background, ecology and eco-epidemiology on a microscale but also at a country and region level, due to possible local adaptations of tick populations and genetic drift. In the present systematic revision, Perez et al. (2023) combine old and recently published data (mostly up to 2020) regarding I. ricinus distribution, phenology, host range and pathogen association in continental France and Corsica Island. Based on a keyword search of peer-reviewed papers on seven databases, as well as other sources of grey literature (mostly, thesis), the authors have synthesized information on: 1) Host parasitism to detect potential differences in host use comparing to other areas in Europe; 2) The spatiotemporal distribution of I. ricinus, to identify possible geographic trends in tick density, variation in activity patterns and the influence of environmental factors; 3) Tick-borne pathogens detected in this species, to better assess their spatial distribution and variation in exposure risk. As pointed out by both reviewers, this work clearly summarizes the information regarding I. ricinus and associated microorganisms from European France. This review also identifies remaining knowledge gaps, providing a comparable basis to orient future research. This is why I chose to recommend Perez et al (2023)'s preprint for Peer Community Infections. REFERENCES Aeschlimann, A., Burgdorfer, W., Matile, H., Peter, O., Wyler, R. (1979) Aspects nouveaux du rôle de vecteur joué par Ixodes ricinus L. en Suisse. Acta Tropica, 36, 181-191. Dantas-Torresa, F., Otranto, D. (2013) Seasonal dynamics of Ixodes ricinus on ground level and higher vegetation in a preserved wooded area in southern Europe. Veterinary Parasitology, 192, 253- 258. Hoogstraal, H., Aeschlimann, A. (1982) Tick-host specificity. Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen Entomologischen Gesellschaft, 55, 5-32. Medlock, J.M., Hansford, K.M., Bormane, A., Derdakova, M., Estrada-Peña, A., George, J.C., Golovljova, I., Jaenson, T.G.T., Jensen, J.K., Jensen, P.M., Kazimirova, M., Oteo, J.A., Papa, A., Pfister, K., Plantard, O., Randolph, S.E., Rizzoli, A., Santos-Silva, M.M., Sprong, H., Vial, L., Hendrickx, G., Zeller, H., Van Bortel, W. (2013) Driving forces for changes in geographical distribution of Ixodes ricinus ticks in Europe. Parasites and Vectors, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-6-1 Perez, G., Bournez, L., Boulanger, N., Fite, J., Livoreil, B., McCoy, K., Quillery, E., René-Martellet, M., Bonnet, S. (2023) The distribution, phenology, host range and pathogen prevalence of Ixodes ricinus in France: a systematic map and narrative review. bioRxiv, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.18.537315 Velez, R., De Meeûs, T., Beati, L., Younsi, H., Zhioua, E., Antunes, S., Domingos, A., Ataíde Sampaio, D., Carpinteiro, D., Moerbeck, L., Estrada-Peña, A., Santos-Silva, M.M., Santos, A.S. (2023) Development and testing of microsatellite loci for the study of population genetics of Ixodes ricinus Linnaeus, 1758 and Ixodes inopinatus Estrada-Peña, Nava & Petney, 2014 (Acari: Ixodidae) in the western Mediterranean region. Acarologia, 63, 356-372. https://doi.org/10.24349/bvem-4h49 | The distribution, phenology, host range and pathogen prevalence of *Ixodes ricinus* in France: a systematic map and narrative review | Grégoire Perez, Laure Bournez, Nathalie Boulanger, Johanna Fite, Barbara Livoreil, Karen D. McCoy, Elsa Quillery, Magalie René-Martellet, and Sarah I. Bonnet | <p style="text-align: justify;">The tick <em>Ixodes ricinus</em> is the most important vector species of infectious diseases in European France. Understanding its distribution, phenology, and host species use, along with the distribution and preva... |  | Animal diseases, Behaviour of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecohealth, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Epidemiology, Geography of infectious diseases, Interactions between hosts and infectious ag... | Ana Sofia Santos | 2022-12-06 14:52:44 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Jorge Amich

Christine Chevillon

Fabrice Courtin

Christine Coustau

Thierry De Meeûs

Heather R. Jordan

Karl-Heinz Kogel

Yannick Moret

Thomas Pollet

Benjamin Roche

Benjamin Rosenthal

Bashir Salim

Lucy Weinert