Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date▼ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

28 Oct 2022

Development of nine microsatellite loci for Trypanosoma lewisi, a potential human pathogen in Western Africa and South-East Asia, and preliminary population genetics analysesAdeline Ségard, Audrey Romero, Sophie Ravel, Philippe Truc, Gauthier Dobigny, Philippe Gauthier, Jonas Etougbetche, Henri-Joel Dossou, Sylvestre Badou, Gualbert Houéménou, Serge Morand, Kittipong Chaisiri, Camille Noûs, Thierry deMeeûs https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6460010Preliminary population genetic analysis of Trypanosoma lewisiRecommended by Annette MacLeod based on reviews by Gabriele Schönian and 1 anonymous reviewerTrypanosoma lewisi is an atypical trypanosome species. Transmitted by fleas, it has a high prevalence and worldwide distribution in small mammals, especially rats [1]. Although not typically thought to infect humans, there has been a number of reports of human infections by T. lewisi in Asia including a case of a fatal infection in an infant [2]. The fact that the parasite is resistant to lysis by normal human serum [3] suggests that many people, especially immunocompromised individuals, may be at risk from zoonotic infections by this pathogen, particularly in regions where there is close contact with T. lewisi-infected rat fleas. Indeed, it is also possible that cryptic T. lewisi infections exist but have hitherto gone undetected. Such asymptomatic infections have been detected for a number of parasitic infections including the related parasite T. b. gambiense [4]. References

[2] Truc P, Büscher P, Cuny G, Gonzatti MI, Jannin J, Joshi P, Juyal P, Lun Z-R, Mattioli R, Pays E, Simarro PP, Teixeira MMG, Touratier L, Vincendeau P, Desquesnes M (2013) Atypical Human Infections by Animal Trypanosomes. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 7, e2256. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002256 [3] Lun Z-R, Wen Y-Z, Uzureau P, Lecordier L, Lai D-H, Lan Y-G, Desquesnes M, Geng G-Q, Yang T-B, Zhou W-L, Jannin JG, Simarro PP, Truc P, Vincendeau P, Pays E (2015) Resistance to normal human serum reveals Trypanosoma lewisi as an underestimated human pathogen. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology, 199, 58–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molbiopara.2015.03.007 [4] Büscher P, Bart J-M, Boelaert M, Bucheton B, Cecchi G, Chitnis N, Courtin D, Figueiredo LM, Franco J-R, Grébaut P, Hasker E, Ilboudo H, Jamonneau V, Koffi M, Lejon V, MacLeod A, Masumu J, Matovu E, Mattioli R, Noyes H, Picado A, Rock KS, Rotureau B, Simo G, Thévenon S, Trindade S, Truc P, Reet NV (2018) Do Cryptic Reservoirs Threaten Gambiense-Sleeping Sickness Elimination? Trends in Parasitology, 34, 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2017.11.008 [5] Ségard A, Roméro A, Ravel S, Truc P, Gauthier D, Gauthier P, Dossou H-J, Sylvestre B, Houéménou G, Morand S, Chaisiri K, Noûs C, De Meeûs T (2022) Development of nine microsatellite loci for Trypanosoma lewisi, a potential human pathogen in Western Africa and South-East Asia, and preliminary population genetics analyses. Zenodo, 6460010, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6460010 | Development of nine microsatellite loci for Trypanosoma lewisi, a potential human pathogen in Western Africa and South-East Asia, and preliminary population genetics analyses | Adeline Ségard, Audrey Romero, Sophie Ravel, Philippe Truc, Gauthier Dobigny, Philippe Gauthier, Jonas Etougbetche, Henri-Joel Dossou, Sylvestre Badou, Gualbert Houéménou, Serge Morand, Kittipong Chaisiri, Camille Noûs, Thierry deMeeûs | <p><em>Trypanosoma lewisi</em> belongs to the so-called atypical trypanosomes that occasionally affect humans. It shares the same hosts and flea vector of other medically relevant pathogenic agents as Yersinia pestis, the agent of plague. Increasi... |  | Animal diseases, Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Eukaryotic pathogens/symbionts, Evolution of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Microbiology of infections, Parasites, Population genetics of hosts, in... | Annette MacLeod | 2022-04-21 17:04:37 | View | |

08 Dec 2022

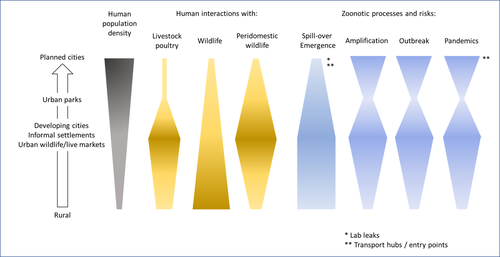

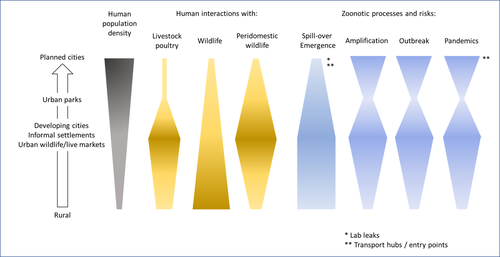

Zoonotic emergence at the animal-environment-human interface: the forgotten urban socio-ecosystemsDobigny, G. & Morand, S. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6444776Zoonotic emergence and the overlooked case of citiesRecommended by Etienne Waleckx based on reviews by Eric Dumonteil, Nicole L. Gottdenker and 1 anonymous reviewerZoonotic pathogens, those transmitted from animals to humans, constitute a major public health risk with high associated global economic costs. Diseases associated with these pathogens represent more than 60% of emerging infectious diseases and predominantly originate in wildlife (1). Over the last decades, the emergence and re-emergence of zoonotic pathogens have led to an increasing number of epidemics, as illustrated by the current Covid-19 pandemic. There is ample evidence that human impact on native ecosystems such as deforestation, agricultural development, and urbanization, is linked to spillover of pathogens from animals to humans (2). However, research and calls to action have mainly focused on the importance of surveillance and prevention of zoonotic emergences along landscape interfaces, with special emphasis on tropical forests and agroecosystems, and studies and reviews pointing out the zoonotic risk associated with cities are scarce. Additionally, cities are sometimes wrongly seen as one homogeneous ecosystem, almost exclusively human, with a Northern hemisphere-biased perception of what a city is, which fails to take into account the ecological and socio-economic diversities that can constitute an urban area. Here, Dobigny and Morand (3) aim to draw attention to the importance of urban ecosystems in zoonotic risk and advocate that further attention should be paid to urban, peri-urban and suburban areas. In this well-organized and well-documented review, the authors show, using updated literature, that cities are places where massive contacts occur between wildlife, domestic animals, and human inhabitants (thus constituting spillover opportunities), and that it is even likely that human and wildlife contact in urban centers is more prevalent than in wild areas, perhaps contrary to intuition. Indeed, cities currently constitute the most important environment of human life and are places for millions of close interactions between humans and animals, including pets and domestic animals, wild animals through the intrusion of wild urban-adapted species (e.g., some bat, rodent, or bird species among others), manipulation and consumption of wildlife meat, and the existence of wildlife meat markets, which all constitute a major risk for zoonotic spillover. In cities, lab escapees of zoonotic pathogens also exist, and trends of adaptation to urban ecological conditions of many vectors of primary health importance is also a concern. The authors further argue that cities are predominant places for both epidemic amplification of human-human transmitted pathogens, because they are places with high human densities and population growth, and for dissemination of reservoirs, vectors and pathogens, as they are transport hubs. Dobigny & Morand further predict, likely correctly, that cities may be important places for pathogen evolution. Finally, they propose actions and recommendations to limit the risk of zoonotic spillover events from urban ecosystems and future directions for research aiming at assessing this risk. The reviewers found the manuscript well-organized and presented, timely, and bringing novel contributions to the field of zoonotic emergence. I strongly recommend this article, which should benefit a large audience, particularly in the context of the current Covid-19 pandemics and the ongoing One Health initiatives aiming at preventing future zoonotic disease emergence (4). References (1) Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, Daszak P (2008) Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature, 451, 990–993. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06536 (2) White RJ, Razgour O (2020) Emerging zoonotic diseases originating in mammals: a systematic review of effects of anthropogenic land-use change. Mammal Review, 50, 336–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/mam.12201 (3) Dobigny G, Morand S (2022) Zoonotic emergence at the animal-environment-human interface: the forgotten urban socio-ecosystems. Zenodo, 6444776, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6444776 (4) Morand S, Lajaunie C (2021) Biodiversity and COVID-19: A report and a long road ahead to avoid another pandemic. One Earth, 4, 920–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.06.007 | Zoonotic emergence at the animal-environment-human interface: the forgotten urban socio-ecosystems | Dobigny, G. & Morand, S. | <p style="text-align: justify;">Zoonotic emergence requires spillover from animals to humans, hence animal-human interactions. A lot has been emphasized on human intrusion into wild habitats (e.g., deforestation, hunting) and the development of ag... |  | Disease Ecology/Evolution, Ecohealth, Ecology of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Evolution of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, One Health, Zoonoses | Etienne Waleckx | 2022-04-11 11:39:11 | View | |

21 Jul 2022

Structural variation turnovers and defective genomes: key drivers for the in vitro evolution of the large double-stranded DNA koi herpesvirus (KHV)Nurul Novelia Fuandila, Anne-Sophie Gosselin-Grenet, Marie-Ka Tilak, Sven M Bergmann, Jean-Michel Escoubas, Sandro Klafack, Angela Mariana Lusiastuti, Munti Yuhana, Anna-Sophie Fiston-Lavier, Jean-Christophe Avarre, Emira Cherif https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.10.483410Understanding the in vitro evolution of Cyprinid herpesvirus 3 (CyHV-3), a story of structural variations that can lead to the design of attenuated virus vaccinesRecommended by Jorge Amich based on reviews by Lucie Cappuccio and Veronique Hourdel based on reviews by Lucie Cappuccio and Veronique Hourdel

Structural variations (SVs) play a key role in viral evolution, and therefore they are also important for infection dynamics. However, the contribution of structural variations to the evolution of double-stranded viruses is limited. This knowledge can help to understand the population dynamics and might be crucial for the future development of viral attenuated vaccines. In this study, Fuandila et al (1) use the Cyprinid herpesvirus 3 (CyHV-3), commonly known as koi herpesvirus (KHV), to investigate the variability and contribution of structural variations (SV) for viral evolution after 99 passages in vitro. This virus, with the largest genome among herperviruses, causes a lethal infection in common carp and koi associated with mortalities up to 95% (2). Interestingly, KHV infections are caused by haplotype mixtures, which possibly are a source of genome diversification, but make genomic comparisons more difficult. The authors have used ultra-deep long-read sequencing of two passages, P78 and P99, which were previously described to have differences in virulence. They have found a surprisingly high and wide distribution of SVs along the genome, which were enriched in inversion and deletion events and that often led to defective viral genomes. Although it is known that these defective viral genomes negatively impact viral replication, their implications for virus persistence are still unclear. Subsequently, the authors concentrated on the virulence-relevant region ORF150, which was found to be different in P78 (deletion in 100% of the reads) and P99 (reference-like haplotype). To understand this loss and gain of full ORF150, they searched for SV turn-over in 10 intermediate passages. This analysis revealed that by passage 10 deleted and inverted (attenuated) haplotypes had already appeared, steadily increased frequency until P78, and then completely disappeared between P78 and P99. This is a striking result that raises new questions as to how this clearance occurs, which is really important as these reversions may result in undesirable increases in virulence of live-attenuated vaccines. We recommend this preprint because its use of ultra-deep long-read sequencing has permitted to better understand the role of SV diversity and dynamics in viral evolution. This study shows an unexpectedly high number of structural variations, revealing a novel source of virus diversification and confirming the different mixtures of haplotypes in different passages, including the gain of function. This research provides basic knowledge for the future design of live-attenuated vaccines, to prevent the reversion to virulent viruses. References (1) Fuandila NN, Gosselin-Grenet A-S, Tilak M-K, Bergmann SM, Escoubas J-M, Klafack S, Lusiastuti AM, Yuhana M, Fiston-Lavier A-S, Avarre J-C, Cherif E (2022) Structural variation turnovers and defective genomes: key drivers for the in vitro evolution of the large double-stranded DNA koi herpesvirus (KHV). bioRxiv, 2022.03.10.483410, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.10.483410 (2) Sunarto A, McColl KA, Crane MStJ, Sumiati T, Hyatt AD, Barnes AC, Walker PJ. Isolation and characterization of koi herpesvirus (KHV) from Indonesia: identification of a new genetic lineage. Journal of Fish Diseases, 34, 87-101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2761.2010.01216.x | Structural variation turnovers and defective genomes: key drivers for the in vitro evolution of the large double-stranded DNA koi herpesvirus (KHV) | Nurul Novelia Fuandila, Anne-Sophie Gosselin-Grenet, Marie-Ka Tilak, Sven M Bergmann, Jean-Michel Escoubas, Sandro Klafack, Angela Mariana Lusiastuti, Munti Yuhana, Anna-Sophie Fiston-Lavier, Jean-Christophe Avarre, Emira Cherif | <p style="text-align: justify;">Structural variations (SVs) constitute a significant source of genetic variability in virus genomes. Yet knowledge about SV variability and contribution to the evolutionary process in large double-stranded (ds)DNA v... |  | Animal diseases, Evolution of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Genomics, functional genomics of hosts, infectious agents, or vectors, Viruses | Jorge Amich | Lucie Cappuccio, Veronique Hourdel | 2022-03-11 10:50:50 | View |

14 Nov 2022

Ehrlichia ruminantium uses its transmembrane protein Ape to adhere to host bovine aortic endothelial cellsValérie Pinarello, Elena Bencurova, Isabel Marcelino, Olivier Gros, Carinne Puech, Mangesh Bhide, Nathalie Vachiery, Damien F. Meyer https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.15.447525Adhesion process of Ehrlichia ruminantium to its host cell: the role of the protein ERGACDS01230 elucidatedRecommended by Thomas Pollet based on reviews by Rodolfo García-Contreras and Alejandro Cabezas-CruzAs recently reported by the world organisation for animal health, 60% of infectious diseases are zoonotic with a significant part associated to ticks. Ticks can transmit various pathogens such as bacteria, viruses and parasites. Among pathogens known to be transmitted by ticks, Ehrlichia ruminantium is an obligate intracellular Gram-negative bacterium responsible for the fatal heartwater disease of domestic and wild ruminants (Allsopp, 2010). E. ruminantium is transmitted by ticks of the genus Amblyomma in the tropical and sub-Saharan areas, as well as in the Caribbean islands. It constitutes a major threat for the American livestock industries since a suitable tick vector is already present in the American mainland and potential introduction of infected A. variegatum through migratory birds or uncontrolled movement of animals from Caribbean could occur (i.e. Deem, 1998 ; Kasari et al 2010). The disease is also a major obstacle to the introduction of animals from heartwater-free to heartwater-infected areas into sub-Saharan Africa and thus restrains breeding programs aiming at upgrading local stocks (Allsopp, 2010). In this context, it is essential to develop control strategies against heartwater, as developing effective vaccines, for instance. Such an objective requires a better understanding of the early interaction of E. ruminantium and its host cells and of the mechanisms associated with bacterial adhesion to the host-cell. In this study, the authors. studied the role of E. ruminantium membrane protein ERGA_CDS_01230 in the adhesion process to host bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAEC). After successfully producing the recombinant version of the protein, Pinarello et al (2022) followed the in vitro culture of E. ruminantium in BAEC and observed that the expression of the protein peaked at the extracellular infectious elementary body stages. This result would suggest the likely involvement of the protein in the early interaction of E. ruminantium with its host cells. The authors then showed using flow cytometry, and scanning electron microscopy, that beads coated with the recombinant protein adhered to BAEC. In addition, they also observed that the adhesion protein of E. ruminantium interacted with proteins of the cell's lysate, membrane and organelle fractions. Additionally, enzymatic treatment, degrading dermatan and chondroitin sulfates on the surface of BAEC, was associated with a 50% reduction in the number of bacteria in the host cell after a development cycle, indicating that glycosaminoglycans might play a role in the adhesion of E. ruminantium to the host-cell. Finally, the authors observed that the adhesion protein of E. ruminantium induced a humoral response in vaccinated animals, making this protein a possible vaccine candidate. As rightly pointed out by both reviewers, the results of this study represent a significant advance (i) in the understanding of the role of the E. ruminantium membrane protein ERGA_CDS_01230 in the adhesion process to the host-cell and (ii) in the development of new control strategies against heartwater as this protein might potentially be used as an immunogen for the development of future vaccines. References Allsopp, B.A. (2010). Natural history of Ehrlichia ruminantium. Vet Parasitol 167, 123-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.09.014 Deem, S.L. (1998). A review of heartwater and the threat of introduction of Cowdria ruminantium and Amblyomma spp. ticks to the American mainland. J Zoo Wildl Med 29, 109-113. Kasari, T.R. et al (2010). Recognition of the threat of Ehrlichia ruminantium infection in domestic and wild ruminants in the continental United States. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 237:520-30. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.237.5.520 Pinarello V, Bencurova E, Marcelino I, Gros O, Puech C, Bhide M, Vachiery N, Meyer DF (2022) Ehrlichia ruminantium uses its transmembrane protein Ape to adhere to host bovine aortic endothelial cells. bioRxiv, 2021.06.15.447525, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Infections. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.15.447525 | *Ehrlichia ruminantium* uses its transmembrane protein Ape to adhere to host bovine aortic endothelial cells | Valérie Pinarello, Elena Bencurova, Isabel Marcelino, Olivier Gros, Carinne Puech, Mangesh Bhide, Nathalie Vachiery, Damien F. Meyer | <p><em>Ehrlichia ruminantium</em> is an obligate intracellular bacterium, transmitted by ticks of the genus <em>Amblyomma</em> and responsible for heartwater, a disease of domestic and wild ruminants. High genetic diversity of <em>E. ruminantium</... |  | Interactions between hosts and infectious agents/vectors, Microbiology of infections | Thomas Pollet | Rodolfo García-Contreras, Alejandro Cabezas-Cruz | 2021-10-14 16:54:54 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Jorge Amich

Christine Chevillon

Fabrice Courtin

Christine Coustau

Thierry De Meeûs

Heather R. Jordan

Karl-Heinz Kogel

Yannick Moret

Thomas Pollet

Benjamin Roche

Benjamin Rosenthal

Bashir Salim

Lucy Weinert